American Philatelic Association

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 The founding members of the APA were not isolated from the transitions of American business and leisure life near the end of the nineteenth century. Robert Wiebe’s influential work, The Search for Order, detailed the breakdown of local autonomy in small “island communities” beginning in the 1870s as hierarchical needs of industrial life took hold in the United States. ((Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877-1920 (New York,: Hill and Wang, 1967).)) In a similar way, the APA sought to join island communities of stamp collectors to form an infrastructure that supported and nationalized the hobby. The founders believed the adage, “in union there is strength,” applied to stamp collecting communities. Bringing national recognition to the hobby, the APA promised to promote philately “as worthy and rational” because “it should be regarded in the same light as are the generally recognized specialties that have worked their way from obscurity to the positions they now apply.” ((American Philatelic Association, Official Circular Number 1, 6. S.B. Bradt, O.S. Hellwig, and R.R. Shuman, “National Organization of Philatelists,” Announcement (Chicago, IL, April 19, 1886), American Philatelic Society Archives, http://www.stamps.org/Almanac/history1.htm.)) Signifying similarities with newly-forming professional associations, these founding members suggested stamp collecting could emerge from obscurity with a formal organization leading the way. By establishing a society of like-minded individuals, philatelists hoped to spread the word about stamp collecting to a national audience.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 On September 14, 1886 the APA held their first meeting to draw up by-laws and a constitution, elect officers, and establish membership and affiliation rules. The small group chose John K. Tiffany, an attorney from St. Louis, Missouri, to be the APA’s first president. By-laws detailed best practices for obtaining stamps and discouraged counterfeiting. According to the preamble of their constitution, the APA would help members learn more about philately, cultivate friendship among philatelists, and encourage an international bond with “similar societies” in other countries. ((By-laws and constitution published in American Philatelic Association, Official Circular Number 1, (November 1886): 2-3, 4-8.)) Philately had a strong international component for all collectors, since most collected and studied stamps printed in countries different from their own. Additionally, the APA believed that connecting with groups outside of the U.S. would raise the stature of this association and make the APA the premiere national philatelic organization. The overall mission of the APA sought to legitimize and publicize the practice of stamp collecting.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Less concerned, rhetorically, with excluding unaffiliated stamp collectors, APA’s constitution encouraged people to join. Technically, “any stamp collector” could apply to the Secretary of APA for membership. Current members considered a candidate’s background for one month before voting to accept or reject petitioners. This procedure was in place to ensure no known counterfeiters applied. Yet if a candidate was not sponsored by another member, chances were high that the application for membership would be denied. This practice mimicked how other exclusive social clubs operated in an attempt to keep out undesirables, namely women and people of color. For an annual fee of $2.00, APA members received the American Philatelist journal, gained access to the APA library, and enjoyed the community of collectors for buying and trading varieties. While embracing all stamp collectors, the APA firmly and publicly rejected those dealing in or making counterfeit stamps. ((American Philatelic Association, Official Circular Number 1, 6.)) By denying membership to known counterfeiters, the APA reassured their members that the stamps they dealt or traded were government-issued stamps.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 While partaking in social gatherings was one aspect of club life, leadership in the APA encouraged a serious study of stamps as part of membership. The second president, Charles Karuth, asked members in 1899 what the APA had done for the “advancement of the science of philately?” Karuth saw its membership comprising mostly of collectors and not philatelists as he carefully distinguished between the “mere amassment of stamps” and the study of philately. So as not to be viewed as “stamp cranks” and to distance themselves from schoolboys who swapped stamps, Karuth encouraged APA members to engage in the valuable and scientific side of philately. If they did this, he believed that philatelists would be “recognized as gentlemen who had chosen a valuable branch of study.” ((Charles P. Karuth, American Philatelist and Yearbook of the American Philatelic Association 8 (1899): 32-4. Much is said about the “science of philately,” yet little is defined within the stamp journals. It seems as if careful study into subject representations on stamps or the specifics about the production of stamps seem to qualify the science.)) Karuth’s plea illustrated how the APA sometimes functioned like a professional association as it distinguished between professionals and amateurs. At the same time, Karuth’s comments also demonstrated a growing tension among club philatelists who wanted to encourage more individuals to collect stamps, but only to do so within strictures established by clubs.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Philatelists stressed that they engaged in rigorous study, and they represented their pursuit with an allegorical figure, “Philatelia,” the Goddess of Philately. Philatelia symbolized their pursuit and may have acted as a guide for those pursuing philatelic knowledge. The APA adopted the image of Philatelia for their seal in 1887 and is still used today. In the seal, Philatelia holds a stamp album in her left hand while she places a stamp into it with her right. As a figurative deity, she sits on a globe that makes her appear larger than the physical world that she sits upon while tending to the stamps kept in her album. Her position suggests that she can control the world on which she sits, gesturing that collecting stamps is symbolically similar to the imperialistic logics that justify how one country believes others are available to be collected and controlled. She is focused on her stamp album appearing studious and unaware of others and is not welcoming or open as she faces away from observers. Her focus on the album and its stamps offers a model for all philatelists who described themselves as “prostrate admirers and worshippers,” and “all in love with one female—the Goddess Philatelia.” ((Philatelia appears as the APA’s seal on the first Year Book from the American Philatelic Association in 1886. Use of Philatelia by other clubs can be found in catalogs such as Rigastamps, Fields-Picklo Catalog of Philatelic Show Seals, Labels, and Souvenirs, May 2005, http://www.cinderellas.info/philexpo/philp-r.htm.. For references to the goddess, see Cullen Brown, “Classes to Collect,” Canadian Journal of Philately 1, no. 1 (June 1893): 15.; and American Philatelic Association, The American Philatelist Year Book 7, no. 13 (1893): 53.))

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Seal of the American Philatelic Association (image courtesy of the American Philatelic Society)

Seal of the American Philatelic Association (image courtesy of the American Philatelic Society)

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Similar to female figures incorporated into other seals and artworks, Philatelia represented the ideals of the APA. Personified representations of America and Columbia, as well as other ideals and virtues, took female forms with which some Americans were no doubt familiar. Iconography similar to Philatelia appeared on public murals in the 1890s, with painted women representing Justice, Patriotism, and the disciplines of science in the Library of Congress. Imagery represented a real political and cultural conflict because some of the principles personified by women were not legally available to them at the turn of the century, including rights to participate in democracy, to make economic choices, and to be protected equally under the law. Similar to these female mural icons, Philatelia celebrated activities that took place predominantly in a male world and was beloved by those men. ((Joshua Charles Taylor, America as Art (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976), 3–34.; and Bailey van Hook, “From the Lyrical to the Epic: Images of Women in American Murals at the Turn of the Century,” Winterthur Portfolio 26, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 63–80.)) We know that women collected stamps privately but were not welcomed in most philatelic clubs. Philatelia, like other female idyllic icons, had limited symbolic powers to represent equality for American women at the turn of the century.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 As the APA and other philatelic groups sought to expand their memberships, they still did not welcome women or people of color. Evidence of white women collecting stamps does not explain why many were turned away from pursuing memberships in stamp societies. First, formal organizations were exclusive and remained that way for many years, and some club names implied they were not for women or girls. The Sons of Philatelia and the Philatelic Sons of America were founded in the 1890s to encourage philately among young people, but sounded like a male-only fraternal organizations. Records indicate, however, that a few female collectors belonged to these organizations, but their numbers remained small. ((Weekly Philatelic Era 9, no. 10 (1894): 91. Often collectors referred in exchanges to their membership number and organization, perhaps to indicate that they were serious collectors. For example, Anna Lambert, of St. Paul, Minnesota, identified herself a member of the Philatelic Sons of America in an exchange notice she submitted to the Weekly Philatelic Era. This identification as a club member may have been more important to a female collector to demonstrate that she was a philatelist and not merely a collector.))

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 With some club names sounding like a fraternal organization, many male collectors believed that philately was in fact a brotherhood—even transforming them into a brotherhood of Renaissance men. Knowledgeable in many subjects, including history, astronomy, geography, and languages, philatelists portrayed themselves as cosmopolitan men of the world. “We Collectors are brothers, comrades, citizens of a great, progressing, ever-widening Brotherhood.” ((Gordon H. Crouch, “On Collecting,” American Philatelist 28, no. 13 (1915): 222.)) This concept of brotherhood was no doubt grounded in ideas learned from experience with fraternal organizations and dinner clubs, and perhaps in saloons, where men socialized in their leisure time. Philatelic club kinship was referred to as “a Freemasonry among Stamp Collectors,” where a fellow collector was “always warmly welcomed.” ((Roy Rosenzweig, Eight Hours for What We Will: Workers and Leisure in an Industrial City, 1870-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985); Swiencicki, “Consuming Brotherhood: Men’s Culture, Style and Recreation as Consumer Culture, 1880-1930.” and “Stamp Collecting as a Hobby,” Weekly Philatelic Era 16, no. 28 (1902): 227-28.))Likening the bonds formed to Freemasonry solidified philatelic clubs—in their minds—as a white male-only domain, while participation in the hobby was not.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Clubs protected the brotherhood by controlling who earned memberships, making philatelic clubs almost exclusively male and white. In the 1880s, a few women applied to join the Staten Island Philatelic Society but never enrolled as members. Rolls from the APA indicate that there were five female members in 1889, but women never became a strong portion of national stamp collecting societies. By 1915, three percent of the Southern Philatelic Association’s membership was women. Most women, it appears, gave up on applying to clubs created in the late nineteenth century, as only one percent of total applicants to the American Philatelic Society (the renamed APA) in 1925. By the mid-1920s, some women turned to newer and smaller stamp societies where the membership rules were less stringent. Even as late as 1990, one of the most exclusive clubs still did not allow female members. ((American Philatelic Association , List of Members of the American Philatelic Association, 1889 (Ottawa, IL: American Philatelic Association, 1887); Col. Lector, “Filatelic Figures,” American Philatelist 39, no. 6 (March 1926): 362; and Christ, “The Adult Stamp Collector”, 91. Cheryl Ganz, Curator of Philately at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Postal Museum, threatened legal action against the Collectors Club of Chicago because they did not accept female members. They acquiesced and she became a member. Cheryl Ganz, conversation with author, May 25, 2007, Washington, D.C.))

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 These clubs were not welcoming for people of color, either. Surprisingly, as African Americans established fraternal, religious, and social clubs on their own terms, stamp collecting appears to be almost absent from their leisure time clubs. ((David G. Hackett, “The Prince Hall Masons and the African American Church: The Labors of Grand Master and Bishop James Walker Hood, 1831-1918,” Church History 69, no. 4 (December 2000): 770-802. I also found that there was a Tuskegee Philatelic Club in 1940 for the issuing of the Booker T. Washington stamp, but it’s unclear to me when the club began. “Tuskegee Philatelic Club Prepares Booklet On Art,” The Chicago Defender (National Edition), January 27, 1940.)) And yet, an African American publisher, who later became the Assistant Registrar to the US Treasury, re-constituted the Washington Philatelic Society (WPS) in 1905 together with white Washingtonians and became the club’s first president. Cyrus Field Adams was a well-known businessman as editor and publisher of The Appeal who used his position at the paper and in various advocacy organizations to argue for political and economic rights of African Americans. He also loved to collect stamps and amassed a collection over 6,000 when he served as the Washington Philatelic Society president. His presence in a white-dominated, “exclusive” club displeased some philatelists from other societies. Rumors were generated that spread through African American newspapers, and even in the New York Times, that Mr. Adams was passing as white and in his position denied another African American philatelist membership in the WPS. Adams had in fact voted for the applicant whose membership was denied by a majority of the other members. ((“For President of the United States Senator Joseph Benson Foraker of Ohio for Vice-President of the United States,” Washington Bee, June 29, 1907, sec. XXVII, Issue: 5, 4; “Capital’s Negroes Fight White Negro: Black Professor Was Barred from Cyrus Field Adams’s Philatelist Society. Race Leaders are Angry Declare Adams Poses as a White Man and Will Seek His Dismissal from the Treasury,” New York Times, June 11, 1907, 7.“Washington Letter,” Rising Son

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 While African Americans were not welcomed into most philatelic clubs, it is probable that some were familiar with the practices of collecting through philatelic literature. Stamp trading and buying often occurred through the mails and one did not have to identify themselves by race or gender to participate. In philatelic literature, individuals identified as African American are almost completely absent until the 1930s when they appear in pejorative and cartoonish ways. ((Examples include: G.R Rankin and Al Pois, “Philatelic Tragedies,” American Philatelist 43, no. 5 (February 1930): 220.; “A Fiji Variety,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 46, no. 45 (November 7, 1932): 555. and “A Specialist in Turkey,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 46, no. 47 (November 21, 1932): 580.)) The comics and jokes printed in philatelic magazines remind us that while philatelists were uniquely engaged within their hobby’s community, they were not isolated from broader American social and cultural behaviors and discourse where racial stereotyping and racism was common.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 As philatelic societies grew and established their membership criteria, they also carved out identities for their organizations and collectors. From its beginnings, the APA set forth to build a strong national philatelic organization in the U.S. designed to compete with British and continental European nations that had already formed their own national philatelic clubs. ((Bradt, Hellwig, and Shuman, “National Organization of Philatelists.”)) To be on par with other national association, the APA articulated a vision in a few key ways.

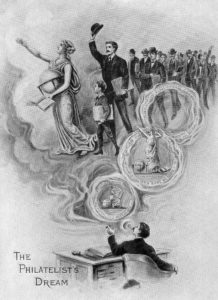

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 First, the APA’s desire to lead in philatelic pursuits came in the form of actual vision. , “The Philatelist’s Dream,” an illustration printed in 1906 demonstrated how the APA could be a leading stamp society in the world. ((“The Philatelist’s Dream (illustration),” American Philatelist and Yearbook of the American Philatelic Association 20 (1906): np.)) In the “Dream,” a vision emerges from a philatelist’s cigar smoke rings while he sits at his desk with his stamp album open. The first smoke ring approximates the APA’s seal with Philatelia sitting on a globe studying her album. In the next ring, Philatelia turns towards the viewer with her album on the floor, and stretches as if she has awoken from a dream. The third ring is empty, as if Philatelia left the APA’s seal. She appears above the three rings holding the globe and stamp album in her arms as she extends her right arm in an action of leadership and movement. Boys, men, and at least one woman follow the APA’s Philatelia as she leads them west across the image.

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

“The Philatelist’s Dream,” illustration (image courtesy of the American Philatelic Society)

“The Philatelist’s Dream,” illustration (image courtesy of the American Philatelic Society)

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 The APA’s image represents a striking similarity to late-nineteenth century art representing American destiny and progress, as the APA envisioned itself as a leader in the philatelic world. The “Philatelist’s Dream” is reminiscent of the 1872 painting “American Progress,” by John Gast that was distributed widely and sold in lithograph form.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

“American Progress,” chromolithograph, published by George Coffut, 1872 (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

“American Progress,” chromolithograph, published by George Coffut, 1872 (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 The female figure wears the “Star of Empire” and floats above people leading them and approving of their westward movement as settlers from the east proceed west across the painting. Settlers push out herds of buffalo and Native Americans, with trains, stage coaches, and ships bringing more settlers to complete the conquering of peoples and lands. The female figure carries a book in hand, not unlike Philatelia’s album, symbolizing knowledge and learning. This awakening of the APA’s Philatelia suggests that club philatelists internalized a vision of America as a unique place with a distinctive history, extending that exceptionalism to their philatelic association. Through this imagery we see that some club philatelists equated studying and collecting stamps with the cultural of imperialism. As the U.S continued to conquer North America and islands in the Pacific and Caribbean, American stamp collectors became leaders in conquering the world in their philatelic knowledge and also in the ways that they amassed nations, stamp by stamp.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 The second part of the APA’s exceptionalist vision included an organizational theme song first presented at the 1906 annual meeting.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 “Rah! For the American Philatelic Association”

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Verse 1: Listen now! Ye nations all,

To our Philatelic song,

That shall tell the story of the A.P.A;

The Association great,

Of a Nation big and strong,

Which for enterprise most surely leads the way.¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Chorus: ‘Rah! ‘Rah! ‘Rah! For the A.P.A.;

It’s the pride of the U.S.;

For it holds in loving thrall

Stamp collectors great and small,

And throughout the world its power is manifest.¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Verse 2: From Atlantic’s rugged coast

To Pacific’s Golden Gate,

And from Southland’s gulf to shining northern lakes,

Are the mighty bounds from which,

Representing every state,

A.P.A its worthy membership takes.¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Verse 3: And its members, they are true

To Philately’s good cause,

Making A.P.A. their ever-guiding star;

For it is a tie that binds,

By its strong but simple laws

That most wonderful and wise in nature are.¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Verse 4: So, we hear from Europe’s marts,

Round the world to Isles of Spice,

Hearty commendations given A.P.A;

And the nations each declare,

“We would give a handsome price

Could we learn the art of building in such way.” ((Karuth, American Philatelist and Yearbook (1899): 34; and “Rah! For the American Philatelic Association,” American Philatelist 20 (1906): 57.))

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Similar to the “Dream”, these lyrics demonstrated that members enthusiastically believed that the APA’s would provide a leading example in the international philatelic world and amply represented the “big and strong” United States. This organization of white male philatelists paired evenly with American foreign policy that constructed a narrative of masculine progress and “manifest” destiny that justified occupations and invasions of sovereign nations. (( Kristin L Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).; and Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease, eds., Cultures of United States Imperialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993).)) Rhetorically, the APA constructed itself to be as strong, and perhaps as masculine, as the United States had become in the geopolitical landscape. The lyrics call out to the world’s philatelists to notice the APA’s strength that comes from its members—“great and small,” “representing every state.” For its members, the APA stands as the “ever-guiding star,” which is almost equivalent to Gast’s “Star of Empire,” leading philatelists to gain new philatelic knowledge, and also to become a leader in philately. Much like the “Dream,” the lyrics indicate how APA members internalized the idea of American exceptionalism—of the U.S. as a nation and with regard to APA. The APA certainly was not the only club with members hailing from all states, but its members believed it stood for ideals of America that those trading and collecting stamps in marts in Europe and Asia recognized the APA’s strength as an organization.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 The “Philatelist’s Dream” and theme song added to a grand vision the APA’s members held for its organization as it expanded and faced competition from other organizations. The last components of this vision came in 1908 when the APA changed its name to the American Philatelic Society (APS) and increased the frequency of publishing its journal. The name change made the APS sound similar to the well-established Royal Philatelic Society, and possibly distanced itself from professional associations that it initially mimicked. The APS started publishing its journal, American Philatelist, quarterly rather than yearly, and American Philatelist began soliciting and printing articles that focused on the study and history of stamps rather than merely publishing the minutes and speeches from the annual conventions. Members were constantly encouraged to recruit acquaintances, and membership nearly tripled from 574 in 1895 to over 1500 in 1908. ((American Philatelist 22, no. 1 (1908): 72, 141; John W. Scott, “A Few Lines from the President,” American Philatelist 31, no 6 (1917): 86-7; and Casper, “All Together for the Good of the A.P.S.,” 134-6.)) As many other stamp clubs formed, the APS relied on its members to help connect smaller clubs to the APS through affiliations. The network of philatelic clubs grew across the US together with an active philatelic press that spread the word about stamp collecting to interested readers while simultaneously recruiting new members.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

Leave a comment on paragraph 25

0 Comments on paragraph 26

Leave a comment on paragraph 26

0 Comments on paragraph 27

Leave a comment on paragraph 27