¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 As we’ve seen, the Interwar years in the US brought tremendous interest in local and regional history, and commemoration of colonial and Revolution-related events. These activities continued into the 1930s with a big booster: the federal government. During Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, federal participation in, influence, and supervision of historical interpretation, practices, and preservation grew tremendously through a number of Depression-era programs. Prior to Roosevelt’s election, public history work was very de-centralized. Congress hesitated to take over locally-controlled sites when asked, while other sites maintained a strong legacy of female management through heritage societies who fought to keep interpretative control over sites they cared for. ((Patricia West, Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1999).))

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 There was no national archive or federal history museum system, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum divided its exhibition space among collections many fields in the arts and sciences. Interest in promoting local and regional traditions continued as more Americans researched their family histories with help from genealogical bureaus that assisted researchers and encouraged individuals from non-elite families to discover their ancestral roots. These strong localized components complemented federal history initiatives during the New Deal. For example, folklore received attention as an essential building block of American culture. The Federal Writers’ Project, Federal Art Project, the Historical American Building Survey, for example, employed hundreds of artists, historians, writers and elevated their work in communities across the country as nationally-significant. Through these programs, the federal government demonstrated a serious commitment to preserving history from the ground up in a way that had not been in the past. ((Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Knopf, 1991), 411–73.))

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The expansion of the National Park Service (NPS) into historic preservation and interpretation is seen as a watershed moment for federal involvement in spreading historical knowledge and in constructing professional public history practices. In 1933, newly-elected Franklin D. Roosevelt officially consolidated all federally-managed battlefields and historic sites under the management of the NPS under the direction of Harold Albright. Prior to 1933, the Park Service focused on the conservation of natural resources and interpretation of geological history in their national parks, rather than on interpreting human history. Albright established a museum program that opened the door for historical interpretation to co-exist in national parks alongside beautiful scenery and physical science research. Professional historians, like Verne Chatelain, were hired to create interpretative strategies for sites, and to develop criteria for selecting new parks. Guiding the selection of new sites was the idea that all parks would be connected across a narrative arc representing “important phases” in American history. This approach privileged event-based sites over person-driven sites—battlefields over birthplaces. Some states, like Minnesota, had already developed a robust program for integrating a state-driven narrative across multiple sites for the NPS to borrow. Early Park Service historians shaped a national narrative about the American past by connecting sites across different states. With many locally-run sites petitioning for inclusion in the new park system, NPMS developed practices for negotiating with local boosters about the conditions for acceptance. These practices would hold for decades to come and firmly established “history as a function of government service.” ((Denise D. Meringolo, Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History (Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 95–105; 153; John E Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1992), 177–81.))

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The USPOD had been involved in history work since the late nineteenth century with its commemorative program, but that work never included historians. NPS officials were much more systematic in their approach to selecting sites for federal protection and interpretation. They developed criteria based on persistent themes they devised for major time periods to construct a progressive narrative of the American past. ((Meringolo, Museums, Monuments, and National Parks, 123–4.)) In contrast, the UPSOD never turned to or employed historians for guidance in making their commemorative selections. Instead, the office of the Third Assistant Postmaster General in consultation with the Postmaster General—political appointees—balanced the requests, and pressure, from citizens and their Congressional representatives when selecting which episodes carried national significance. By the time the NPS sought suggestions for new historic parks, civic boosters and history enthusiasts already knew they could petition their government to ask that their favorite historic site, event anniversary, or hero represent the United States through publication on a postage stamp. NPS may have benefited from the USPOD’s established process.

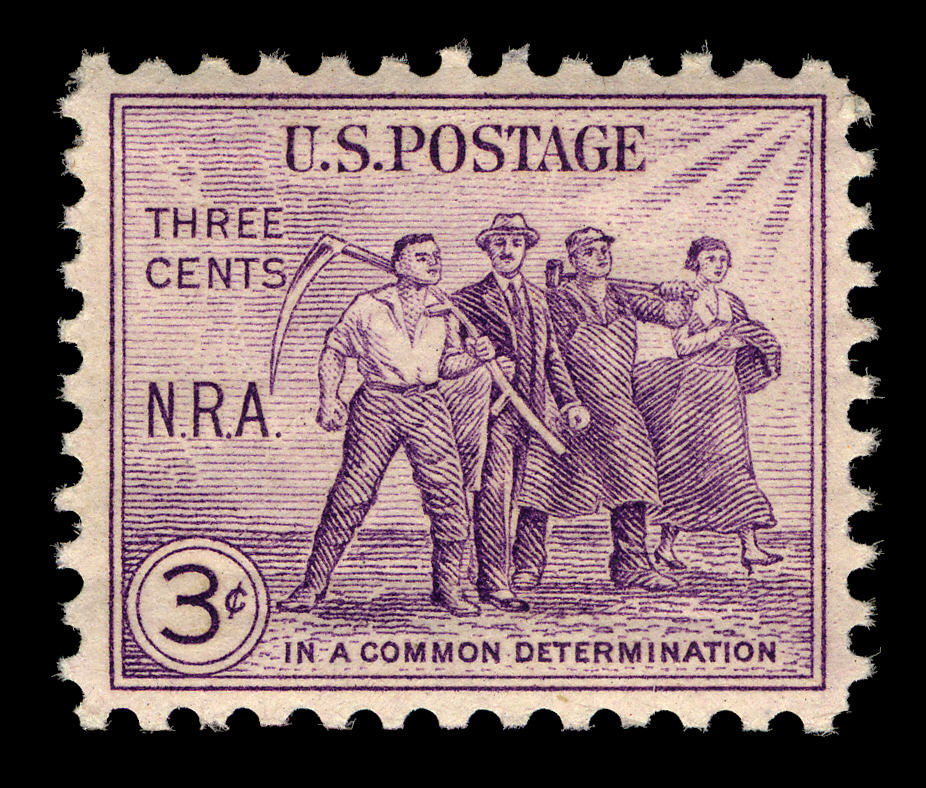

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Letter writing campaigns to the USPOD continued into the 1930s, as civic and political groups saw there was power in circulating messages on stamps. Beginning in 1933, we see that commemorative selections retreat from featuring regional and local anniversaries, and instead focus on celebrating state anniversaries, broad national themes, and supporting contemporary federal programs. We can attribute this shift directly to the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He used the commemorative stamp program to build popular support for his federal initiatives. He understood that the visual language of stamps, printed by the USPOD, carried great power and could reach large numbers of Americans. Stamp collecting already appealed to many different people in first half of twentieth century and as a philatelist, FDR saw collecting grow as a hobby from the nineteenth into the twentieth century. During FDR’s first term, the USPOD printed more special commemoratives than in previous administrations. ((Thomas J. Alexander, “Farley’s Follies,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum), accessed June 21, 2009, http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=4&cmd=2&eid=8&slide=toc.)) Individuals and political groups campaigned for stamps to represent African American achievements and women’s suffrage, which came in 1936 and 1940. During these public calls for commemoratives to more fully represent the American past, the USPOD continued its role as an arbiter of cultural symbols. Stamp collecting surged in popularity during the Depression years, and more individuals saw, saved, and valued commemoratives as miniature memorials. When saved in an album, collectors reviewed and reflected on a stamp’s imagery and often researched the scenes and individuals represented. Subjects chosen to represent the US on a commemorative stamp lived on beyond the time period of their issue. For the first time, a president who was an avid collector, directly influenced stamp selection and production.

You might want to cite some books on the specific programs. Taken as a whole, these works describe this as a period in which there was a serious effort to “document” America’s traditions and communities. These efforts were (perhaps ironically) fueled by a sense of urgency –these were disappearing traditions. So, for example, HABS documented historic structures because many would be demolished. Folk stories were collected before memory of them disappeared. There’s a weird tension between the desire to preserve and the belief that progress necessarily erased these vernacular forms of identity. Jerrold Hirsch: Portrait of America; maybe John Rayburn A Staggering Revolution;

Good suggestion, I’ll take a look at this again. Your point about tension is well taken, especially as I think about these stamps being collected and cared for as the real thing–as pieces of national identity–vs traces of the real vernacular things–HABs documentation.