Supporting Exploration, from the Poles to the Parks

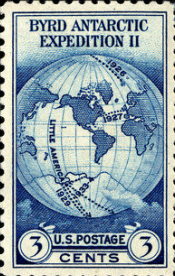

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Another stamp printed in 1933 came as a suggestion from President Roosevelt that supported an expedition to Antarctica led by Admiral Richard E. Byrd. Designed for philatelic purposes, the Philatelic Agency (PA) sold the stamp.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Byrd Antarctic Issue, 1933 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

Byrd Antarctic Issue, 1933 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 If collectors wanted their stamps to be canceled at the Little America post office by the expedition crew, they sent a self-addressed stamped envelope with a postal mail order for fifty-three cents to the expedition’s headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia, or to the PA. Covers were gathered and sent down to the “most southerly” post office. Byrd served as a naval (reservist) officer and scientist who had explored regions near the North and South Poles, during his career. He also was a close friend of FDR’s who supported this expedition. Byrd secured private financing for his polar journeys, and but the expeditions were expensive. While FDR did not divert federal dollars towards Byrd’s second Antarctic exploration (1933-34), FDR did facilitate a path allowing the proceeds from the limited issue commemorative stamp to go towards the expedition expenses.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 FDR even sketched the stamp’s design and encouraged others to help the expedition by buying the stamps. Byrd’s expedition team carried the letters with a special 3-cent stamp to the Little America camp, where each piece of mail would be canceled with a seal from Antarctica by a newly appointed postmaster for the outpost. Because of the distance carried, a fifty-cent transportation fee was imposed. This fee helped finance the expedition’s transportation expenses. Postal workers Leroy Clark and Charles Anderson were overwhelmed by the volume of mail and canceled more than 150,000 envelopes in Little America. ((“Byrd Stamps Explained,” New York Times, September 27, 1933, 16; “The Stamp Album,” Washington Post, October 29, 1933, sec. For the Washington Post Boys and Girls, 4.; “Philatelic Notes,” Washington Post, December 9, 1934, sec. ST, 10.; and Mary H. Lawson, “Byrd Antarctic Issue,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (National Postal Museum, February 1, 2007), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=2&tid=2033020; Johl, The United States Commemorative Stamps of the Twentieth Century, 261–66.))

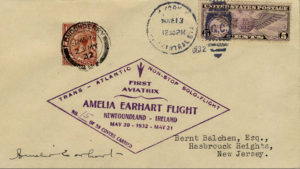

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Example of the mails Earhart carried with her, May 20-21, 1932. (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

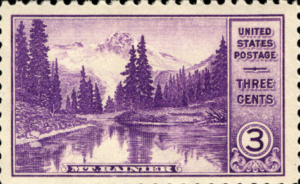

Example of the mails Earhart carried with her, May 20-21, 1932. (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Prior to Byrd’s expedition, another pioneer relied on philatelic funding for her travels. Amelia Earhart also carried mail with her on her first transatlantic flight in May 1932, but her flight was not authorized by the USPOD. Instead, philatelists paid her to postmark each of 50 letters in Newfoundland and after landing in Ireland, and she numbered and autographed each cover. News spread through philatelic circles and Earhart carried mail with her on additional flights. She also saved and exhibited examples of her stamped envelopes, or covers, at philatelic exhibitions. On her final, fatal, flight she carried approximately $25,000 in souvenir envelopes . ((Cheryl Ganz, “Amelia Earhart’s Solo Transatlantic Mail,” National Postal Musuem, Object of the Month, May 2007, http://postalmuseum.si.edu/museum/1d_Earhart_Mail.html; “Amelia’s Plane Bears $25,000 of Stamp Fan Mail,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1937, sec. PART 1, 2.)) Sales of the Earhart covers and the Byrd stamp contributed to the expenses of both Earhart’s and Byrd’s expeditions. Earhart appealed directly to philatelists for her support; Byrd appealed to his friend the president and was officially supported by the federal government.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 The Department received many negative responses from philatelists who did not approve of federal promotion of the Byrd expedition through sales from a commemorative issue. Unlike other limited-issue commemoratives, these stamps were only available through the Philatelic Agency and not at local post offices. The souvenir covers were also sold at Gibmel’s department store, as were Earhart’s for her final flight in 1937. ((“Amelia’s Plane Bears $25,000 of Stamp Fan Mail,” 2; “Gimbel’s to Sell Byrd Stamps,” New York Times, December 23, 1933, 3.)) This move led to confusion as to whether stamps could be redeemed to mail a letter in US because the USPOD designed the 3-cent Byrd for philatelic purposes only. While the stamp could be used as regular postage, this issue was not commemorative. Philatelic community reactions against this type of current event limited-issue did not spawn a protest of the likes seen in 1898 over the Trans-Mississippi issues. While some philatelists complained, no one began a massive letter-writing campaign. In fact, many Americans thought this was a worthy cause because the Philatelic Agency sold over six million Little America stamps. Admiral Byrd wrote to FDR expressing his gratitude, saying that the stamp “helped us immeasurably in a number of ways.” The stamp and cancellation from a remote post office offered a new way to publicize the Antarctic expedition and Byrd welcomed the increased exposure. ((Eilenberger, “Speech Delivered to American Philatelic Society,” 5; “Byrd Stamps Explained,” 16; “The Stamp Album,” 4; “Philatelic Notes,” 10; and Lawson, “Byrd Antarctic Issue.” Lynn Heildelbaugh, “Antarctic Post Office,” National Postal Museum, November 2008, http://www.postalmuseum.si.edu/museum/1d_Antarctic_PO.html.))

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

Little America post office overrun with covers awaiting cancellation. ( Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

Little America post office overrun with covers awaiting cancellation. ( Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 FDR continued to capitalize on the Department’s ability to promote federal programs in the 1930s by encouraging the printing of a series highlight the growing network of national parks. Declaring 1934 as the National Park Year, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes worked closely with PMG Farley to create a 10-stamp series featuring picturesque scenery from ten parks. Issued in rapid succession primarily during summer months, the series was designed to encourage domestic tourism. ((Gordon T. Trotter, “National Parks Year Issue,” Arago: People, Postage, and the Post, November 27, 2007, http://arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2033094.)) A collector could buy all ten and assemble them as if they had traveled across the US visiting those natural wonders.

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

National Parks Mt. Rainier 3c issue (Smithsonian National Postal Museum collection)

National Parks Mt. Rainier 3c issue (Smithsonian National Postal Museum collection)

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 The National Parks Year also coincided with the expansion of the National Park Service to include battlefields and historic sites. None of the new sites appeared in this series, but the stamps reinvigorated interest in the federally-managed park system. Without naming a New Deal program, this series also subtly promoted the work of the newly-created Civilian Conservation Corps. Beginning in 1933, the CCC employed hundreds of thousands of young men who built infrastructure at national parks and forests across the US. Tourists, collectors, or relatives of CCC workers might decide to buy one or more stamps in the National Park series.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Once again, this limited issue series did not represent a historical narrative, but rather, promoted contemporary government initiatives. Roosevelt’s administration showed its acumen for marketing federal programs by piggy-backing on the success of Post Office’s commemorative stamp program. Stamp sales increased and the receipts from the Philatelic Agency during fiscal year 1935 were the highest to date. This growth was seen by the USPOD as “further evidence of the increasing attention that is being directed to stamp collecting.” ((“National Parks Commemorative Series Sale Sets Record: Ten Varieties Are Offered In Picked Postoffices and D.C. Most Important Question Settled Is That Place an Issue Honors Is Fitting One for a First-Day Presentation.,” The Washington Post, October 21, 1934, A11; United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1935 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1935), 44–46.)) Popular participation in and media attention of stamp collection was beginning to peak nationwide.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Federal efforts to unite Americans during an economic depression included stamps in their portfolio that showcased the beauty of National Parks, the common determination of citizens, and the achievements of explorers enduring extreme condition for scientific research. Another Rooseveltian effort to promote feelings of nationalism came with a series of stamps honoring military heroes. The announcement of this series surfaced regional, gender, and racial tensions, while also questioning who qualified to represent national character on US commemoratives.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13