Revolutionary Heroes from Poland

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Polish Americans and immigrants fought to honor two Polish Revolutionary War heroes on stamps as part of a larger strategy to portray Polish Americans as good Americans with ancestral ties to the birth of the United States as a nation.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 In the 1920s, Congress overwhelmingly approved immigration restrictions that imposed strict quotas on individuals arriving from Eastern and Southern Europe. Restrictions came in reaction to both political concerns over post-World War I radicalism and eugenically-influenced charges of racial inferiority based on biology (see Anniversaries and Immigration Policy). Poles, for example, were described as a distinct “race” of people. ((Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (University of California Press, 1985) and Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color, 1998. During a Kosciusko Day celebration in New York City, for example, the mayor referred to Poles as a separate “race.” See “5,000 Hear Mayor Praise Kosciusko,” New York Times, October 16, 1933, 19. )) Few legislators spoke out to oppose the quotas. Representative Robert H. Clancy, however, defended immigrants for their positive contributions to the US including the Polish:

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Polish-Americans are as industrious and as frugal and as loyal to our institutions as any class of people who have come to the shores of this country in the past 300 years.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Clancy also mentioned the contributions of Polish citizens during the Revolution that demonstrated a “high place” they had earned in American history. ((Robert H. Clancy, >em>Congressional Record (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1924), 6529–32.)) Polish-American groups broadcast those achievements of their Revolutionary War heroes to anchor their people as loyal Americans, worthy of citizenship.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

General Count Casimir Pulaski Memorial, Washington, DC. Dedicated 1910 (Photograph taken by Wally Gobetz, 2009 , Flickr.com.

General Count Casimir Pulaski Memorial, Washington, DC. Dedicated 1910 (Photograph taken by Wally Gobetz, 2009 , Flickr.com.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Efforts began in the early twentieth century to recognize the contributions of Count Casimir Pulaski and General Thaddeus Kosciuszko with statues and postage memorials. In 1910, monuments honoring both men were dedicated in Washington; Pulaski’s financed by Congress and Kosciuszko’s donated to “the people” by the Polish American Alliance. ((“Monuments of Two Polish Heroes to Be Unveiled in Washington May 12,” The Atlanta Constitution, May 11, 1910, 1; “Nation to Honor Polish Patriots,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 9, 1910, 6. For stamps that were eventually approved, such as those honoring Thaddeus Kosciuszko (Design files, #734), see rejection letters for why petitions were denied for specific years in the stamp’s design file.)) Pulaski was a Polish nobleman who volunteered to fight for the colonies and is known as the Father of the American Calvary. He fought and died at the Battle of Savannah in 1779 and the city honored him as a local hero. To further extend Pulaski’s reputation as a national hero, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution spearheaded a stamp campaign in 1929. They co-sponsored an anniversary commemorating the 150th anniversary of the fall of Count Pulaski at the battle of Savannah, Georgia. Supporting the DAR’s efforts to secure a stamp was Georgia Congressman Charles Edwards, who petitioned the Postmaster General to support a Pulaski commemorative and commented that “the Daughters of the American Revolution would not sponsor anything that is not real meritorious and entirely worthy.” According to Edwards, the DAR properly vetted the stamps’ subject matter and passed their patriotic test and possibly upheld Pulaski as an early model Polish immigrant. Honoring Pulaski as a war hero was not in question when President Herbert Hoover declared October 11, 1929 as “Pulaski Day,” yet no stamp came. ((“Savannah Exalts Pulaski’s Memory,” New York Times, October 6, 1929, N1; Telamon Culyer, “Sesqui-Centennial of Georgia’s First Clash of Armies,” The Atlanta Constitution, October 6, 1929, J1; “Notable Fete Is Planned to Honor Pulaski,” The Washington Post, October 6, 1929, S5. In Design Files (#690): Bernice E. Smith, “Letter to Congressman Charles G. Edwards,” letter, April 5, 1929; Charles G. Edwards, “Letter to Honorable Walter F. Brown,” April 6, 1929; American Consul Central, “Letter to Honorable Secretary of State,” September 23, 1930.)) Hoover and Congress acknowledged Pulaski as a national hero, but earning a commemorative stamp proved more difficult.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

Von Steuben Issue, 1930 (Photo, Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

Von Steuben Issue, 1930 (Photo, Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Surprisingly the following year, strong rebukes came from a Polish newspaper that may have influenced the government’s decision to print a Pulaski commemorative. The paper accused U.S. postal authorities of using a “double standard” when choosing whom to honor on stamps with the headline, “Polish Proposition Refused—Germans Favored.” According to this paper’s editor, the USPOD honored a German Revolutionary War hero, Baron Frederic Wilhelm von Steuben, on a stamp but refused to reciprocate for a Polish Pulaski.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 French newspaper editors even decried the choice of the von Steuben stamp. They did not seek a Pulaski stamp, but rather sought recognition for French military officers who fought for independence, including Lafayette and Rochambeau. Missing from the correspondence file were panicky or angry letters from government officials strongly urging the Postmaster General announce a Pulaski stamp quickly. A few months later, however, nearly fifteen months after the Savannah anniversary celebration, a Pulaski issue was announced. ((Design Files (#690): Bernice E. Smith, “Letter to Congressman Charles G. Edwards,” letter, April 5, 1929; Charles G. Edwards, “Letter to Honorable Walter F. Brown,” April 6, 1929; American Consul Central, “Letter to Honorable Secretary of State,” September 23, 1930.)) This episode demonstrates that the world noticed when a government printed new stamps, placing postal officials in a challenging role. Their decisions held enormous political weight and carried cultural meaning far beyond those petitioning for stamp subjects.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 This can been seen in the ways that non-collecting Americans noticed new stamps and questioned the reasoning behind postage choices. Present in the design files for the Pulaski stamp was an angry letter from an American who asked why the USPOD honored Pulaski with a stamp and did not chose an American soldier instead. She spoke of her fears of first-generation immigrants held by many fellow citizens. Mrs. M.A. Van Wagner criticized Polish immigrants for coming to the U.S. only to “get employment here and take our American dollars back to Poland” while others remained unemployed (presumably she meant native-borns) in the early years of the Depression. For Van Wagner, the Pulaski stamp signified another way that America had been “forgnised” similar to the “gangs” of foreigners who were responsible for importing “poison” liquor during Prohibition. ((M. A. Van Wagner to Postmaster General, 2 January 1931, Design Files,(#690) )) Her letter stands alone in the Pulaski file as one of protest, but her emotional reaction to this stamp reflects real sentiments felt by some Americans in the interwar period not only towards eastern European immigrants, but also in the power she felt stamps possessed in representing, or perhaps misrepresenting in this case, an official narrative of the U.S. Stamps may have been small, but their images were powerful.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Many Americans supported immigration restrictions of Johnson-Reed, so viewing an eastern European, Pulaski, on a stamp may have angered them. It seemed hypocritical of the government to limit immigration of specific groups of people because they were not considered fit for citizenship, and then a few years later honor an individual representing one those inferior groups on a federal stamp. This occasion was not the first time the US government recognized the achievements of Pulaski, but the accessibility of a commemorative stamp meant that more people—across the United States and around the world—saw first-hand that the federal government celebrated a Polish hero as an American one.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

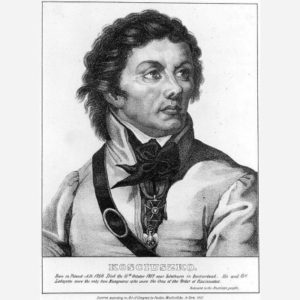

Tadeusz Kosciuszko, lithograph, 1833 (Image, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery)

Tadeusz Kosciuszko, lithograph, 1833 (Image, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery)

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Concurrent to the Pulaski stamp campaign, petitions arrived at the USPOD seeking a stamp to honor another Polish Revolutionary War hero, Thaddeus Kosciuszko. At the time of his death in 1817, Poles and Americans mourned his legacy as a war hero and his commitment to fighting for liberty worldwide. His legacy continued on in the form of monuments and celebrations dedicated in his honor. ((Gary B Nash, Friends of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, Tadeusz Kościuszko, and Agrippa Hull: A Tale of Three Patriots, Two Revolutions, and a Tragic Betrayal of Freedom in the New Nation (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 207–213. Interestingly, Kosciuszko was an amateur artist who sketched Thomas Jefferson. See some examples at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, http://npgportraits.si.edu/emuseumCAP/code/emuseum.asp?style=single¤trecord=1&page=search&profile=People&searchdesc=Name%20contains%20Kosciusko……&searchstring=Name/,/contains/,/Kosciusko/,/false/,/false&newvalues=1&rawsearch=constituentid/,/is/,/10335/,/false/,/true&newstyle=text&newprofile=CAP&newsearchdesc=Related%20to%20Tadeusz%20Kosciuszko&newcurrentrecord=1&module=CAP&moduleid=1)) Among those commemorative efforts was one to immortalize his legacy on a postage stamp that would reach across the U.S. and abroad to his homeland Poland. The Kosciuszko Foundation first petitioned the Postmaster General in 1926, by way of New York Senator Royal S. Copeland to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the general’s “coming” to the colonies. ((Senator Royal S. Copeland, “Letter to Postmaster General Harry S. New,” April 29, 1926, Design Files (#734). ))

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 After those attempts failed, queries were reshaped and the Foundation asked for a stamp that would instead honor the 150th anniversary of his “naturalization as an American citizen.” From 1931 to 1933, hundreds of endorsement letters arrived in the office of the Postmaster General supporting this stamp, accumulating a greater volume than supported Pulaski’s stamp just a few years earlier. Seven years after the first requests, Postmaster Farley fittingly chose to announce the Kosciuszko issue on Polish Day at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago. Farley claimed that he was “happy to convey (his) highest regard for the American citizens of Polish extraction” and declared that Kosciuszko’s name would be “forever perpetuated in the hearts of American people.” ((Design file (#734) Copeland to New, 29 April 1926; Senator Couzens (MI), S.J. Res. 248 “Authorizing the Issuance of a Special Postage Stamp in Honor of Brig. Gen. Thaddens Kosciuszko,” S.J. Res. 248, Congressional Record, 74 (February 6,1931) p.4121. The design file is filled with letters of support coming from individuals, politicians, businessmen, and fraternal organizations. Information Office, Post Office Department, press release, July 22, 1933. ))

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Citizenship was a key element in pitching this stamp, which also was reflected in the announcements printed in newspapers. Kosciuszko’s “admission to American citizenship” and the “privilege of becoming a citizen” were celebrated alongside his military service. Much like Farley who paid homage to Polish citizens, other reactions to the issue emphasized that the General’s legacy on a stamp “honors not only the man himself, but his countrymen who have come by the hundreds of thousands to the country he helped to establish as a land of liberty for all men.” ((“Stamp to Honor Kosciusko,” New York Times, July 23, 1933, 13; Richard McPCabeen, “The Stamp Collector,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 13, 1933, D4; “The Stamp Album,” The Washington Post, August 20, 1933, SMA3; and Editorial, “Honoring Kosciusko,” Hartford Courant, July 27, 1933.)) Whether Kosciuszko actually became an American citizen was not questioned at the time, but the stamp offered a strong symbolic gesture and honor for all people with Polish heritage as bestowed upon them by the government. They were nation builders, too.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Choosing to honor Kosciuszko’s “naturalization” proved to be a curious claim made by the Foundation. There appears to be no documentary evidence to support the claim that he became an American citizen, even though he was held in high regard and called a friend by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and other Revolutionary War-era notable figures. After the War, Kosciuszko haggled with the new Congress, like other soldiers, to be paid back wages for his service in the Continental Army. He earned membership in the Society of the Cincinnati, which was limited to military officers who served during the Revolution. Kosciuszko returned to his native Poland to where he led resistance against Russian occupation and fought, unsuccessfully, against Russian occupation and oppression. He published the “Act of Insurrection,” similar to the Declaration of Independence, and also freed the serfs in Poland in 1794. After some initial victories, Kosciuszko’s resistance was crushed by the Russian forces and he was taken prisoner and held in Russia. A few years later he returned to the United States, committed to freeing his homeland. ((An excellent telling of Kosciuszko’s travails and travels can be found in Nash, Friends of Liberty.))

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Kosciuszko hoped to lobby support for Polish independence from American and French governments but found himself politically opposed to John Adams’s anti-France policies. In light of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, Thomas Jefferson urged Kosciuszko to leave the country to avoid imprisonment. If Kosciuszko had been naturalized, he would not have needed to flee the country. According to Congressional records in 1976, Representative John H. Dent tried to rectify that by submitting a resolution to confer citizenship upon Kosciuszko, perhaps in the spirit of the Bicentennial celebrations. Kosciuszko’s actual status was less important than the way that Polish-American cultural groups constructed his historical identity as an American citizen. ((Nash, Friends of Liberty. Regarding the stamp, I found some correspondence from 1986 in the design file that asked then-curator of the National Postal Museum where they could find documentary evidence of Kosciuszko’s naturalization. The curator said there was no documentary evidence and attached a letter written in 1953 to the Director of the Public Library of Newark stating that there was no official “naturalization, but that through his deeds and actions he became an ‘American’.” See also Representative Dent, (PA), H.J.Res.771, Joint Resolution to Confer U.S. Citizenship Upon Thaddeus Kosciusko, Congressional Record, 122, (January 21,1976) p.544.)) These groups believed there was a lot at stake by representing Kosciuszko as a citizen as well as a military hero. Polish immigrants and Polish Americans were conflicted, much like immigrants and citizens of Norwegian descent discussed earlier, about how best to balance their cultural and political identities as Poles and as Americans.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Unlike the Norse-American stamps which depicted ships and represented migration, the Pulaski and Kosciuszko stamps depicted each man in very different ways.

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

General Pulaski, 2-cent, 1931 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

General Pulaski, 2-cent, 1931 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0

Pulaski visually is associated with Poland with his portrait flanked by the modern flags of Poland and the United States. Generally, other commemoratives did not print the U.S. flag. Pulaski’s portrait appears in the center where he casts his glance to his left, to the side where the Polish flag appears from behind his portrait. In contrast, the Kosciuszko design did not feature either flag. Perhaps because the stamp commemorated the 150th anniversary of his “naturalization” as an American citizen, flags were not necessary for indicating his nation of origin; Kosciusko was American, Pulaski was Polish. ((Max G Johl, The United States Commemorative Stamps of the Twentieth Century (New York, H.L. Lindquist, 1947), 268–9.))

The final design represented Kosciuszko standing as a military officer, distinguishing him from other Revolutionary War citizen-soldier stamps, and instead identified him as a leader.

¶ 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

Kosciuszko, 5-cent, 1933 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Kosciuszko, 5-cent, 1933 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 The stamp engraving reproduces the full-bodied statue of that sits in Lafayette Park across from the White House in Washington. Kosciuszko appears larger than life as he looks down upon the stamp reader from his pedestal. Like many other Revolutionary War officers represented on stamps, he is standing, not on horseback, with sword drawn and appears ready to lead a battle. Pulaski, who was a royal Count, looks out from his portrait wearing a dress military uniform. Oddly, he is not on horseback although he is credited as founding the American Calvary. No identifying language tells a stamp consumer that Pulaski died at the Battle of Savannah. And unless one read the newspaper announcements discussing the stamp, or as a collector purchased the first day cover, the average American probably did not understand that the dates printed on the Kosciuszko, 1783-1933, celebrated his fictional naturalization. ((The first day cover stamped in Kosciuszko, Mississippi, reads that he became a citizen by an act of Congress in 1783, perpetuating the myth of naturalization. See: “734-11a 5c Kosciuszko, Kosciusko MS, 10/13/33, S, UNKN DESIGNER (Blue Env),” eBay, accessed December 31, 2013.))

¶ 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

The first day cover stamped in Kosciuszko, Mississippi reads that he became a citizen by an act of Congress in 1783, (Photo from eBay).

The first day cover stamped in Kosciuszko, Mississippi reads that he became a citizen by an act of Congress in 1783, (Photo from eBay).

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Obtaining these commemoratives were great achievements for the fraternal and Polish heritage organizations that fought for these stamps to demonstrate ethnic pride and claim a piece of American heritage, and as another means for establishing their status as racially white. Their members experienced discrimination and understood that Poles and other eastern European immigrants were defined as racially different from old stock immigrants hailing from western Europe, even as cultural and legal definitions of whiteness were changing in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. Celebrating Kosciuszko’s naturalization tells us that it was important for the Polish National Alliance, Polish Roman Catholic Union, and other organizations to broadcast their hereditary claims to Revolutionary lineage, and American citizenship. The first naturalization law in 1790 dictated that only a “free white person” was eligible for citizenship. Kosciuszko qualified as white and fit for citizenship, countering justifications behind restricting immigrants from Poland in the Quota Act and Johnson-Reed. In the early twentieth century, Polish-Americans were inching their way out of an in-between status, racially, and used the accomplishments of two Polish military men who volunteered (and died, in Pulaski’s case) for the American cause during Revolutionary War as their connection to the origin of the republic. ((Roediger, Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White, The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs; Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color, 1998.))

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Polish-American groups received help from the USPOD in proving themselves as fit and historically local American citizens since their ancestors helped to found the United States. The legal and cultural murkiness of racial classification in the early twentieth century made it more imperative for first and second generation immigrants to be able to stake their claim to whiteness. For Polish immigrants, earning two stamps helped.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

Leave a comment on paragraph 25