Order within Stamp Albums

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Philatelic clubs and papers played an important role by setting and circulating standards for stamp collecting practices, including ways to properly care for and maintain a stamp collection. Novices learned that philatelists did not keep stamps in cigar boxes or decorate furniture with stamps, as some women’s magazines encouraged. Rather, philatelists ordered the world of stamps in their albums. Albums protected stamps from deteriorating, and in subtle ways marked gender differences between collectors. By setting standards of collecting and modeling that behavior, club collectors, who were overwhelmingly male, distinguished themselves as philatelists while others who collected stamps were mere collectors.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 To begin training collectors in the proper way to care for and maintain a collection, some philatelic literature offered primers on collecting for novices. Young readers learned how to start collecting with the ABC of Stamp Collecting. Philatelists admonished novices to care for their collections properly, because “nothing detracts more from the interest and value of any collection, than a slovenly, careless and dirty arrangement.” ((“Stamp Collecting as a Hobby,” 227-28; and Fred J. Melville, ABC of Stamp Collecting (London: Drane, 1903).)) This only matters, of course, if an individual collected for the purpose of re-selling their stamps or participating in a public exhibition.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Keeping stamps in albums offered collectors a neat and orderly space to organize and display their stamps. The first albums appeared in France in the 1860s as publishers began printing albums in Europe and the United States. Early albums were organized visually by geography: first by continent, then region within the continent, and last by country. Later albums listed countries alphabetically, including colonial headings such as “German East Africa” or “British Guyana.” ((Lewis G. Quackenbush, “The Evolution of the Stamp Album, from Lallier to Mekeel,” Philatelic Journal of America, (Reprinted by Earl P.L. Apfelbaum,1894, available at: http://www.apfelbauminc.com/library/evolutionalbum.html.)) Albums forced an organizational structure, by country and denomination, but also provided blank pages for an individual to augment an album with issues not represented in the pages or to collect in their own schema. Albums also protected stamps from human and environmental damage and separated stamps designated as collectors’ items from stamps purchased to mail a letter. While some albums were custom-made, say for British royalty, most were commercially produced by publishers or dealers and sold by stamp and novelty shop owners. For some examples of albums, see the National Postal Museum collection.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Cover, Scott’s International Postage Stamp Album, 1912 (author’s collection)

Cover, Scott’s International Postage Stamp Album, 1912 (author’s collection)

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Cover, Scott’s Imperial Stamp Album, 1919 (eBay item)

Cover, Scott’s Imperial Stamp Album, 1919 (eBay item)

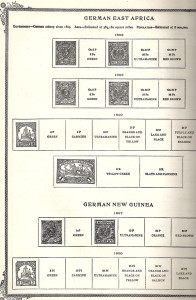

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 An album offered the collector an apparatus to classify and display stamps from different countries, empires, and colonies, giving the appearance that a collector held the world in their albums. For example, Scott’s “International” and “Imperial” albums offered spaces to hold collections of all varieties of postage stamps printed, while Mekeel’s created albums for specialists in Mexican or American stamps from North and South America. Order was dictated in an album so that the collector placed stamps from a specific geographical location in a specific place. When flipping through an “International” album, one found maps of continents and regions that represented national borders but not states or provinces within each country. In the map pages, we find North and Central America first, and then localities follow in alphabetical order after the stamps of the U.S. ((Quackenbush, “The Evolution of the Stamp Album, from Lallier to Mekeel”; The International Postage Stamp Album (New York: Scott Stamp and Coin Co. Limited, 1894); The International Postage Stamp Album, Nineteenth Century Edition (New York: Scott Stamp and Coin Co. Limited, 1912); “1919 Scott Stamp & Coin Imperial Stamp Album (eBay Item accessed August 14, 2009); “Old Scott Stamp Co. Imperial Stamp Album 450+ Stamps!! – (eBay Item, accessed August 11, 2009.)) Selling to American customers, it is not surprising that Scott’s privileged the U.S. map and American stamps within this international album. American exceptionalist narratives were prevalent in commemoratives, as will be discussed later, and these ideas were present in American album design as well.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Philatelists bought and traded countries, represented in stamps, and then ordered the world in their albums. This process was influenced by an imperialistic view of the world where imperial powers fought over lands, natural resources, and peoples in an effort to gain an economic and political edge. An individual stamp collector chose which countries to collect and then made an effort to achieve that goal. As a virtual representation of the globe, an album offered collectors the opportunity to show off their stamps and glimpse the holdings of others with an eye towards acquiring those countries as well. Collectors occasionally spoke of their collections in this imperialistic way. Verna Hanway described how many philatelists fondly laid their eyes upon a valuable stamp sitting in an album with the “pride of a conqueror.” ((Verna Weston Hanway, “Firelight Reveries,” Philatelic West and Camera News 31, no. 2 (November 1905): np.)) One could create their own miniature empire within their own collections held in albums.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Page from Scott’s International Postage Stamp Album, 1912 (author’s collection)

Page from Scott’s International Postage Stamp Album, 1912 (author’s collection)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 As albums imposed order in a collection, they also acted a tool to encourage consumption by highlighting the empty spaces. An empty space meant there was still a stamp left to buy. Dealers often published albums and reminded consumers that albums provided “a valuable and necessary aid in providing for a collection,” while also selling stamps to help fill those albums. ((“1919 Scott Stamp & Coin Imperial Stamp Album – eBay item accessed August 11, 2009.)) Albums also reflected how well a collector cared for their stamps, and philatelists judged one another based on the condition and size of a collection kept inside. Philatelists spent much of their time carefully placing stamps in their appropriate slots within an album. This also meant each time he or she opened an album, empty spaces stared back. These albums represented checklists, of sorts, that guided a collector when making future purchases or trades. Empty spaces motivated many collectors to fill them, and went unseen when one kept stamps in a box. Some collectors saved money to buy an expensive stamp or two that might complete a set, or that might give them something desirable to someone else for future bartering. Albums forced order, while also encouraging consumption.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Albums also facilitated looking at stamps in certain ways that made them appear like souvenirs from an international shopping spree. Physically visiting a foreign country was not necessary for acquiring stamps as souvenirs because an individual acquired stamps through dealers or exchanges, or from fellow collectors at club meetings. Souvenirs offered an incomplete vision of an authentic place or experience that allows the consumer or recipient to create their own narrative surrounding that new object, which delighted some collectors. ((Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1984).)) H.R. Habicht found great romance in the idea that a French Napoleon stamp “witnessed” the commune in Paris and then was carried to South Africa with its new British owner only to be auctioned off after the Boer War to someone who would later donate it to the Berlin Postal Museum. ((H.R. Habicht, “The Enjoyment of Stamp Collecting,” American Philatelist 36, no. 4 (1922): 159-61.)) Stamps gave people like Habicht an opportunity to connect with the past and create their own memories of events or places that they had never experienced. Stamps, then, held a transformative power for some philatelists who created memories for stamps and sometimes projected themselves into the stamp’s past life.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Verna Hanway romanticized about the stories hiding in the pages of album. Engaging in a collection was an intimate experience that involved the collector’s personal context of memory. For Hanway, remembering “the old days” was one of the pleasures of a collection:

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 But you and I fellow collectors, hold its memory as something tender and sacred. Others, materialists, may deem it a madness, but if this be madness, “there is a pleasure in being mad, which none but madmen know. ((Hanway, “Firelight Reveries.”))

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Stamps told stories to Hanway. Her album brought her closer to those stories and the personal memories she associated, or created, with stamps. She distinguished collecting stamps from a practice merely for the sake acquisition. Mining these personal relationships forged through stamps is difficult for historians who can only see stamps carefully placed in an ordered album, but cannot read the meta-narrative present for the collector.

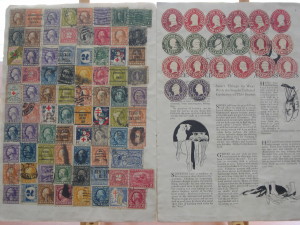

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Gathering evidence of different ways that people collected and illustrated their own narratives through their stamps proves difficult because philatelic standards do not recognize collecting conventions falling outside of standard album keeping. Handmade albums or decorative stamp pieces are often discarded because the philatelic community places little or no value on them. For example, the album pictured below is worthless in the eyes of auctioneers today. Someone made this album using a local department store catalog and reinforced it with cardboard. The collector gummed—without the hinges typically used with a philatelic album—inexpensive stamps and stamp-shaped stickers to each page in colorful patterns over the illustrations of women modeling the new winter line of coats. Created during World War I, this collector designed a red cross in stamps that may have been a way that this person remembered those wounded in war. Stamp papers discouraged this type of decoration with stamps and particularly discouraged gumming stamps directly to paper. ((This particular piece was rescued by Cheryl Ganz, Curator of Philately at the National Postal Museum, because it had no value at an auction. Someone planned to throw it away but thought Ms. Ganz might enjoy it because of her work. )) This collection fell outside of philatelic practice enforced by its community. Other examples of women collectors may not have been saved given that there would have been no monetary value.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

Page from homemade stamp album, ca. 1917 (author’s photo, album courtesy of Cheryl Ganz)

Page from homemade stamp album, ca. 1917 (author’s photo, album courtesy of Cheryl Ganz)

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

Page from homemade stamp album, ca. 1917 (author’s photo, album courtesy of Cheryl Ganz)

Page from homemade stamp album, ca. 1917 (author’s photo, album courtesy of Cheryl Ganz)

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Order and classification in albums minimized aesthetic and creative reasons for collecting stamps, which also enforced gender differences between male club philatelists and independent female collectors. Philatelists tried to distinguish themselves as experts in stamp knowledge, and they acquired that knowledge through careful classification and study of stamps as placed in their albums. This meant most disapproved of other ways that people collected and used stamps, particularly in decorating such as when Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1888 printed instructions for creating a postage stamp table. Women readers learned how to gum rare stamps to the top of a small wooden white table and then to glaze over the stamps with a smooth veneer. In 1905, an American woman made a dress that was completely covered with patterns created from over 30,000 stamps. William O. Sawyer papered a twelve-foot square room with over 20,000 United States postage stamps in 1921. Responding to the latter, Philatelic West exclaimed, “oh the affront to philately!” This style of collecting or amassing stamps for the sake of decorating or using stamps in art projects was never recommended in philatelic journals. ((“One Way of Collecting,” The Philatelic West and Collectors World 78, no. 1 (1921): n.p.; and “Work Department,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 101, no. 605 (1880): 477. Reported by London Tid-Bits but reprinted in “Costume of Postage Stamp,” Eagle County Blade, 1905, 3.)) Once used in a decorative way, stamps could not be resold. The value of saving stamps might be considered lost on a decorative project.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Decorating with stamps was more often associated with women than men, which begins to address one of the more puzzling pieces of this history of stamp collecting: how men came to dominate this hobby. Steven Gelber proposes that a commodification of stamps took hold in the 1860s when the earliest collectors began trading stamps and amassing sets. Gelber argues that since stamps represented payment and were classified by country, year, and denomination, those sets possessed “real market value.” Sets were meant to be completed. Male philatelists developed a market model of collecting that they taught to other club philatelists through gatherings and the philatelic press. This model militated against female participation and made stamp collecting feel like a business endeavor and less like a hobby. Stamp dealers set up shops in business districts, such as in Manhattan’s financial district on Nassau Street, furthering the connection between the male world of business and philatelic practices. ((Steven M. Gelber, Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 117–19; Herman Herst, Nassau Street; a Quarter Century of Stamp Dealing, vol 1 (New York, NY: Duell, 1960).)) Caring for a collection in albums not only enforced the idea that stamps needed to be classified properly, but that stamps comprised sets and the sets were meant to be filled. In order to complete one set you might have to break up another, so one protected stamps in case one wanted to sell or trade them. Collectors who decorated with their stamps were not participating in the market model, nor were they studying their stamps carefully for their watermarks or perforation. They collected stamps for fun and because they enjoyed the aesthetics.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Some club philatelists collected in ways based on the stamp as a commodifiable object, but not all male philatelists approved of a completely-market driven model. Some voiced concerns that too many collectors focused on earning money from stamps rather than on the enjoyment of collecting. In 1901, L.G. Quackenbush wrote that the motivation for collectors should be research and hours of enjoyment gleaned from stamps, not the potential for earning money. He berated the collector “whose attachment to Philately is so much a matter of dollars and cents that a decline in the catalogue value of his stamp means a corresponding decline in his pleasure in them.” Quackenbush saw philately as a serious intellectual pursuit and tried to separate its fierce connection with its market side:

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Let us strive to educate the rising philatelic generation to a different standard. Let us teach them that the intellectual and ethical beauties of philately are the keystone of its power, and that its greatest benefits and largest dividends are not in negotiable coin. ((L.G. Quackenbush, “The Sordid Side of Philately,” The Philatelic West 15, no. 2 (April 30, 1901): n.p.))

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 There was a constant tug within the philatelic world between those who believed they were “true” philatelists interested in the education and enjoyment of the hobby and unconcerned with making money, and those who collected stamps to sell and trade in the hopes of earning money. ((“Hobby of Business,” The Philatelic West and Collectors World 79, no. 2 (1922):n.p. Despite the author’s admonition of stamp papers for promoting the lure of the big find, additional articles were printed that featured great finds. In “The Lure of Stamp Collecting,” re-published eight years later in the Philatelic West, N.R. Hoover tells the stories of a few “almost unbelievable” stories of lucrative stamp finds. These stories continue especially into the 30s during the Great Depression. N.R. Hoover, “The Lure of Stamp Collecting,” The Philatelic West and Collectors World, 89, no. 1 (August-November, 1930): n.p. )) As the hobby attracted more followers, the marketability of a stamp collection grabbed the attention of many. The hope of getting rich from finding rare, old stamps in an attic or in a relative’s trunk persisted, even when a majority of collectors never got rich from their stamps.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Even as men controlled philatelic clubs and influences common practices, women still collected and were urged to participate. Verna Hanaway and others urged women to collect because stamps seemed to naturally fit in with women’s interests. Even though Eva Earl found life as female philatelist challenging, she still encouraged other women to participate in this hobby. Noting that stamp collecting was quite usual for “our brothers,” it often was discouraged in girls. She began her collection with duplicates she received from her brother, and then Earl “caught the fever.” She became more curious than ever about the pastime that she described as one of the “most seductive of pursuits.” Schooled in the market model, so to speak, Earl worried that she might not be able to continue collecting because “we girls have little or no money,” unlike “you men, you have every thing.” ((Eva Earl, “A Girl’s Philatelic Reminiscence,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 5, no. 3 (February 1894): 207-08.))

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Even as Earl wrote publicly about her experiences, she was quite aware that she did not have many sisters in philately in 1894. Clifford Kissinger observed that the numbers of female philatelists were quite small and that they were rarely heard from in the philatelic press. His solution was that women needed more encouragement from “the sterner sex,” urging married male collectors to encourage their wives to begin their own albums. Kissinger insisted that “our hobby must appear favorably to the feminine taste” because of the “pleasing colors of many of stamps” and “handsome designs.” Speaking to a mostly male audience, he urged men to, “encourage the ladies—we need their presence, and should gladly welcome them to the ranks, and accord them that recognition to which they are entitled.” ((Clifford W. Kissinger, “The Fair Sex in Philately,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 5, no. 2 (January 1894): 172-73.)) Women definitely collected stamps, but often did not identify as philatelists. The scope of their participation in the hobby is difficult to gauge during the 1880s through the 1920s, because they were excluded from most collecting clubs and were not frequent contributors to stamp papers. Material evidence of their collecting practices and habits most likely were thrown away, much like what almost happened the handmade album shown above.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24

0 Comments on paragraph 25

Leave a comment on paragraph 25