Trans-Mississippi Controversy

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Following the Columbian issues, the UPSOD began engaging philatelists in unprecedented ways and some philatelists, particularly dealers, felt uncomfortable with the new role that the U.S. and other governments played in the stamp market by printing limited-issue commemoratives. This discomfort exploded into a philatelic controversy at the end of the nineteenth century. The U.S. Columbians were among an early group of commemoratives printed by various nations to celebrate “jubilees,” or significant anniversaries and events, in Japan, Portugal, Greece, San Marino, and Hungary. This small flurry of limited-issues angered some philatelists worldwide who deemed them unnecessary and believed that these nations printed the stamps solely to collect revenue from gullible collectors. To protest and dissuade collectors from purchasing such stamps, philatelists in London formed the Society for the Suppression of Speculative Stamps (SSSS). Worried about how a flood of commemoratives would affect stamp prices, the SSSS participated in letter-writing campaigns using the philatelic press to encourage collectors around the world to ignore those stamps. ((“Revolt of Philatelists,” New York Times, March 8, 1896, 22; “The SSSS Is Correct,” The Philatelic West 2, no. 3 (September 1896): 12; J.A. Jamesell, “Commemorative Issues,” The Philatelic West 2, no. 3 (September 1896): 11–12; “Another Scheme,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 6, no. 6 (November 1894): 484. For the San Marino, some philatelists were angered because the republic seemed to favor those ordering large numbers of stamps by sending the stamps in commemorative envelopes (covers) that would be canceled in San Marino. ))

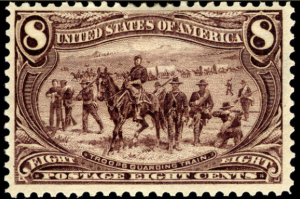

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Two years later, in the U.S., outrage and protest came from philatelists who tried to stop the USPOD from printing a stamp commemorating the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha (1898). Released to promote the fair, the series comprised nine stamps celebrating the conquest of western lands and peoples through imagery of agriculture, such as on the 2-cent, and through technological developments, as found on the 2-dollar. Each stamp carried identifying images of wheat stalks across the top and partially-peeled ears of corn in each bottom corner, both major cash crops farmed in Nebraska and in territories across the Midwest. To safely migrate to new farming lands, federal troops were depicted as protectors of American pioneers from Indian attacks on the 8-cent stamp. America’s imperialistic foreign policy and military aggression was portrayed as a natural outgrowth of westward expansion which was celebrated at the Exposition. ((Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, 105–125.))

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

Farming in the West, 2-cent, 1898 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Farming in the West, 2-cent, 1898 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Troops Guarding Train, 8-cent, 1898 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Troops Guarding Train, 8-cent, 1898 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

Mississippi River Bridge, 2-dollar, 1898 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection

Mississippi River Bridge, 2-dollar, 1898 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Spurring much discussion in the philatelic press, Mekeel’s likened the Trans-Mississippi stamps controversy (for the stamp papers) to what “the Maine incident has been to the wider field of American journalism.” Philatelic editors voiced opinions and collectors responded, meanwhile the press printed articles composed by the newly-formed Stamp Dealers’ Protective Association (SDPA), SSSS, and Scott Stamp and Coin Company who encouraged all philatelists to write in protest to the Postmaster General. They claimed that the proposed commemoratives provided free advertising for the exposition and therefore were not a legitimate use of the postal service. The Columbians, they claimed, “should not be considered a precedent for future issues,” and lamented that philatelists would endure “a sad blow to (their) hobby if the government of the United States should lend itself to so reprehensible a scheme.” Celebrating the founding of the U.S. was an occasion “of such surpassing importance” that the Columbian Exposition was not just about commemorating the fair, but also represented an important anniversary for the nation. According to some protestors, commemorating American settlement of the land west of the Mississippi was only of “passing interest.” Of course, the overall theme of the Exposition and the stamps celebrated the federal government’s role in “settling the west” just as the US military was occupying Cuba and the Philippines. To prevent philatelists from properly saving such unnecessary stamps, Scott Stamp and Coin, one of the largest publishers of international stamp albums, refused to print spaces in their albums for collectors to save “speculative” commemorative stamps from 1897 to 1899. ((“The S.S.S.S. and the Omaha Stamps,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 11, no. 13 (March 31, 1898): 148; American Journal of Philately 9 (January 1898): opening page; “Omaha Exposition Stamps—Protest of San Francisco Collectors,” American Journal of Philately (March 1898): 132; “Omaha Stamps at the S.S.S.S.” American Journal of Philately (May 1898): 209; reprinted memo from John A. Merritt, Third Assistant Postmaster General, American Journal of Philately (September 1898): 374-75; and “Protest of the Postage Stamp Collectors,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 11, no. 7 (February 17, 1898): 78. Letters issued by the Stamp Dealers’ Protective Association were also printed in the mainstream press, such as the Chicago Daily Tribune; “Trans-Mississippi Stamps Issued in Spite of Criticism,” Washington Post, August 12, 1934, AM edition, 7; and “This Busy World,” Harper’s Weekly (January 22, 1898): 79. ))

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 While the SDPA claimed that all collectors viewed the Trans-Mississippi issues as speculative and unnecessary, collectors themselves were conflicted. One individual wrote to the Philatelic West describing his or her joy in collecting commemorative stamps as soon as they were issued. Editors of the Virginian Philatelist endorsed the Omaha Exposition stamps and revealed that they had received only one negative response from a subscriber. These conflicts reflect some growing pains appearing in the philatelic world as it expanded. Philatelic clubs like the American Philatelic Association tried to grow their membership and attract new collectors to the hobby even as members rejected new commemoratives that drew more attention to philately. As the popularity of philately increased, hundreds of philatelic journals circulated around the world, a trend that disturbed some collectors and philatelic journalists. ((H. Franklin Kantner, “Philatelic Journalism,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 3, no. 3 (February 1893): 49–52; H. Frank Kantner, “The Philatelic Writer,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 2, no. 1 (June 1892): 3; H. Frank Kantner, “The Philatelic Publisher’s Soliloquy,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 2, no. 1 (June 1892): 3.; and H. Franklin Kantner, “Philatelic Journalism,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 3, no. 3 (February 1893): 49-52.)) The once small intimate community of collectors had grown and those collectors felt conflicted by its growth and the interest shown by USPOD.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Another reason some collectors hesitated to accept what they viewed as an excessive number of commemorative stamps related to an incident resulting in a stamp market flooded with reprints from Nicaragua, Salvador, Honduras, and Ecuador. This flood resulted from a deal made by Charles Seebeck, an officer of the Hamilton Bank Note Company, who offered to print stamps for no charge to the afore mentioned countries. These stamps, however, actually expired, which was an uncommon practice. A U.S. two-cent stamp issued in 1898, for example, may be affixed to a letter today and combined with other stamps to mail a first-class letter. A Seebeck print, however, was invalid a few years after issued. After the expiration date, Seebeck received permission to reprint that same stamp using the original engraving plates, and he sold those issues to collectors, speculating that the sales covered his costs. Seebeck’s plan resulted in thousands of Latin American stamps entering the stamp market between 1890 and 1898. After Seebeck’s death in 1899, a speculator bought the remaining unused reprints—all ninety million of them—and sold, traded, and gave them away. Many of those reprints landed in starter stamp packets geared to generating interest in young collectors. ((Jack Child, Miniature Messages: The Semiotics and Politics of Latin American Postage Stamps (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 45–7.)) Concerns over the Seebeck issues certainly colored philatelists’ opinions about new commemorative stamps.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Dealers in particular charged all governments with trying to fleece collectors by printing stamps with “fancy designs” that they saw as unnecessary for regular postage. The SSSS and SDPA did not discriminate in their criticism of stamp issuing-nations like others did, because they seemed to be motivated mostly by economic factors and a desire to keep the stamp market controlled by dealers. Oddly, many dealers lacked enthusiasm for commemoratives that drew more people into the hobby of collecting and even argued that jubilees turned people away. One philatelic editorial illuminated this hypocrisy by criticizing dealers for giving away stamps in chewing gum and cigarette packages one minute, while protesting commemorative issues that might more easily attract more collectors another. It was said that limiting the issues of US commemorative stamps, such as for the Pan-American Exposition and Louisiana Purchase, drew enough attention to stamp collecting and would not “fail to be of material value in advancing the collecting hobby, and one which could hardly be termed speculative.” ((“Another Protest,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 11, no. 7 (February 17, 1898): 78; and “Editorial,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 11, no. 7 (February 17, 1898): 78. See Chapter 1 on the relationship between Scott Stamp and Coin and Duke Cigarette company. L. G. Dorpat, “A Year of Philately,” The Philatelic West and Camera News 18, no. 1 (January, 1902); and E. R. Aldrich, “Notes for U.S. Collectors,” The Philatelic West and Camera News 17, no. 9 (December, 1901). This period of World’s Fair promotions after 1894 also marked the beginning of what has been categorized as the “Bureau Period” in philately because it is marks the time when the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), the agency responsible for designing the dies for all American money, took on the contract for designing and printing U.S. stamps exclusively through 1940. For more information on the BEP’s involvement in stamp production, see United States, History of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1862-1962, Reprint ed (New York: Sanford J. Durst, 1978).)) In theory, the injection of stamps into the market that brought new collectors would have given dealers a larger pool of people from which to do business—in person or via the post. Instead, they resisted an expansion and fought the producers of stamps by attempting to maintain their stronghold on the stamp market.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 As philatelists argued among themselves over the appropriateness of the USPOD’s Trans-Mississippi commemoratives, a discussion emerged about the political and cultural status of the U.S. in their rhetoric. The timing of this particular protest is quite striking. This series specifically commemorated an Exposition that celebrated European migration to and conquest of territories across the middle section of the continent home to many Native Americans. Concurrently, the U.S. and its military reached beyond the continental borders to invade and occupy sovereign nations and former European colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific. In defending the USPOD’s production of American commemoratives, stamp columnists and editors stated that the U.S.’s large population required postal services “greater than any other nation on earth” and was “privileged to some philatelic things without censure.” But, “petty states of Asia and Africa,” or “some little bankrupt country” should be rebuked for issuing non-essential postage for the purpose of bringing in revenues. ((Missourieness, “The Proposed Omaha Exposition Stamps,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 11, no. 4 (January 27, 1898): 41–2.; “Editorial,” 78; “Protest of the Postage Stamp Collectors,” 78; N.A. Crawford, “The Progress of Philately,” Philatelic West and Camera News 32, no. 2 (March 1906): no page numbers available.)) The Seebeck issues were no doubt in the minds of some philatelists who held that the United States was unique and should be able to produce postage stamps for whatever purpose postal officials saw as necessary.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 This exceptionalist argument did not merely apply to international philatelic matters, but was another extension of the constructed racial and economic privilege imagined especially by architects of American foreign policy. ((Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease, eds., Cultures of United States Imperialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993); Gary Gerstle, American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).)) Stamps commemorating American world’s fairs celebrated empire and conquest and promoted scientifically-based racial hierarchies leaving “petty states of Asia and Africa” at the bottom, while white America and western Europe rested at the top. Prevailing attitudes towards other nations’ racial composition affected how stamp collectors viewed a state’s ability, or right, to print commemoratives.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 We hear in this rhetoric that collectors believed they influenced the production of stamps and decisions made by governments about their postage, but not everyone agreed. Mekeel’s editors thought it was absurd of the SSSS and the SDPA to think that postal officials would pay attention to philatelists’ protests over stamp production, or that the USPOD would print stamps specifically for collectors. From their observations, Mekeel’s editors believed the USPOD, “almost invariably snubbed collectors wherever possible and given us plainly to understand that it looked upon us with suspicion.” ((“The S.S.S.S. and the Omaha Stamps,” 148–49.)) True or not, the editors of a major philatelic paper believed the USPOD was oblivious to their pursuit.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 These protests highlighted growing pains felt by philatelists as the USPOD, and international postal agencies, acknowledged collectors and printed stamps for them. Prior to the Columbians, the USPOD was not concerned with attracting collectors, but soon after began to influence the stamp market gently by throwing additional stamps in the global collection every few years. Following the Columbian experiment, the Trans-Mississippis cemented the precedent. Interestingly, sixty-four years after the introduction of the postage stamp in the United States, the Department still defended using a postage-based system to collect revenues. Citizens continued to suggest alternatives, but postal officials noted in the Department’s Annual Report of 1911 that the USPOD would expand rather than contract or replace the current stamp system. ((United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1911 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1911), 272–73.; and “A U.S. Service for Philatelists,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 31, no. 6 (February 10, 1917): 51.))

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 And expand, it did. From 1892 to 1919 the USPOD printed 47 different commemorative stamps, almost exclusively to celebrate world’s fairs or regional expositions, including the Trans-Mississippi Exposition (1898), Pan-American Exposition (1901), Louisiana Purchase Centennial (1904), Jamestown Tercentenary (1907), the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (1909), Hudson-Fulton Celebration (1909), and Panama Pacific Exposition (1915). After projected revenues from the Columbians fell short of Wanamaker’s 2.5 million dollar estimate, postal officials commissioned more conservative numbers for all other commemoratives and shortened the period of availability for future series from a year to a few months. Though not attracting nearly as much publicity, these stamps were collected and considered successful endeavors. ((United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1901 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1901); United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1904 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904); and Kenneth A. Wood, Post Dates: A Chronology of Intriguing Events in the Mails and Philately(Albany, OR: Van Dahl Publications, 1985).)) Governments noticed collectors and dealers of stamps and began targeting them for sales. Despite resistance from philatelists to be viewed as consumers, ultimately they could not prevent governments from printing scores of commemorative stamps.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16