What Philately Teaches

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 In 1899, well-known stamp dealer and philatelic writer John N. Luff explained to a crowd gathered at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences newly-established section of Philately what he believed that philately taught its followers. Philately, he asserted, opened up a wide field of research:

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 It trains our powers of observation, enlarges our perceptions, broadens our view, and adds to our knowledge of history, art, languages, geography, botany, mythology and many kindred branches of learning.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The mechanical part of stamp making may be studied with much profit and entertainment. Considered in all its aspects, philately is even more instructive than matrimony.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 It teaches even the unwilling and the careless. In the effort to fill these spaces in their albums they must learn what varieties they are lacking and in what these differ from other and similar varieties. ((John M. Luff, What Philately Teaches: A Lecture Delivered before the Section on Philately of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, February 24, 1899 (New York, NY: n.p., 1915), 4–5, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15713/15713-h/15713-h.htm.))

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Luff and other philatelists believed that learning of some kind was inevitable when collecting stamps, even for those unaware of the process. That learning began, according to Luff, first by looking at a postage stamp. He highlighted for the audience the different design elements and then encouraged them to analyze the physicality of the stamp, including the paper, perforations, and gum. The process of observation, he explained, led stamp collectors to read meaning into stamps, because a stamp was designed deliberately and required interpretation. Luff’s lecture was widely distributed in the early twentieth century and fellow collectors pointed to this book as an excellent primer for introducing stamp collecting to new audiences.

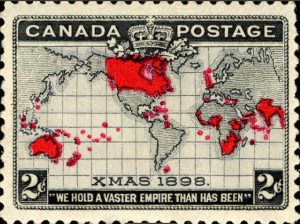

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Collecting, then, made stamps good vehicles for teaching different skills or literacies. Knowledge of current events and political geography, for example, were often cited as benefits to philately. In 1894, one collector wrote that “stamp-collecting brings the situation of every important nation of the earth again and again through life to the mind of the collector.” Referencing the rapidly changing political landscape in south and central Africa amidst the “scramble” by colonizing European empires, philatelists saw themselves as more involved than the average person in current events, because they followed international political developments in newspapers to keep up on new stamp issues. Newly-issued stamps often revealed new governing bodies over previously sovereign territories. In those cases, imperial governments not only constructed and enforced new territorial boundaries with infrastructure and military posts, but also through printing postage stamps that constructed new identities for people living in regions who weren’t necessarily culturally connected. ((Article reprinted from December 1888: J.W. Scott, “Stamps of the United States Sanitary Fairs,” American Philatelist 32, no. 3 (December 1918): 61–3.; “History in Stamps,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 21, 1894, 42.; Crawford Capen, “Stamp-Collecting: How and What We Learn From It,” St. Nicholas, An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks, January 1894, 279; and Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (New York: Avon Books, 1992).)) These colonial identities circulated on stamps and became the identity by which collectors and stamp spectators associated with people living in those territories. The needs of empire led to the creation of postage stamps in the 1840s, and sometimes empire was very visible on stamps themselves.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

British Empire on Mercator Map, 2-cent Canada, (photo, Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

British Empire on Mercator Map, 2-cent Canada, (photo, Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Collecting during this period of intense competition for power and sovereignty in Africa and Asia was exciting for philatelists, because it meant new international stamps were regularly available for purchase or exchange. The mainstream and philatelic press constantly informed readers about newly-issued foreign stamps that held power to teach collectors about other countries. As debates and fears over immigration to the U.S. in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries ensued, using stamps to expose adults and children to foreign lands and cultures frequently framed the discourse. In 1910, one Washington and Lee professor praised stamp collecting for teaching geography, the expansiveness of British and European empires, and different systems of money. ((Jas Lewis Howe, “Postage Stamp Collecting,” Christian Observer, March 30, 1910, 19)). The Christian Science Monitor, which took an early interest in stamp collecting by sponsoring regular columns, consistently extolled the values of learning with stamps for keeping children in touch with events around the world and “political and social history.” Parents and children might examine a series of stamps that traced changes in governance, which contributed to the popular belief that stamp collecting taught geography, politics, and history. Collapsing empires, “belligerent nations” occupying territory, and newly independent states all represented the changing geo-political landscape during and following World War I. ((“A Young Collector (photograph),” Christian Science Monitor, July 24, 1934, 6.)).

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Alternatively, stamp collecting offered potential to generate greater cultural exchanges. With a large and growing immigrant population in the US, some groups could have connected the interest in stamp collecting, to learn about Italy for example, from a native-born Italian. Collecting was about the stamps and nation, however, and not necessarily about understanding the individuals or cultural history of the stamp’s originating locale. A collector seeking Chinese stamps in the 1880s might also fully support the Chinese Exclusionary Act. Collectors enjoyed gleaning small tidbits of information about a country from a stamp, which was just another product—or souvenir—from nations, empires, and colonies.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Some collectors described the experience of viewing stamps as being transported virtually to another nation. Images of foreign rulers, holidays, and landscapes carried one teenage girl to that country in her mind. She learned “everything that you would like to know about in any country” from its stamps. Anne Zulioff imagined the journey her stamps took from a printing press onto a precious letter, and then to land into her stamp album. ((H.R. Habicht, “The Enjoyment of Stamp Collecting,” American Philatelist 36, no. 4 (January 1922): 159–161.; and Anne Zulioff, “Stamps,” Washington Post, September 2, 1934, sec. JP, 1.)) In this example, small colored bits of paper acted as an agent activating the imagination. Adults and children learned to look at and read stamps as cultural objects embedded with meaning. That meaning, of course, was subjective and personal. The history and culture Zuiloff described, was imagined.Teaching that global politics and cultures could be understood through the imagery and rhetoric of stamps, encouraged understanding the world in oversimplified ways.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 For many educators, using stamps to teach elementary school-aged children geography and global politics was logical. Stamps were colorful, accessible, and led to discovering basic facts about foreign countries. Additionally, educators incorporated stamps into their classroom, because they believed they were capitalizing on a child’s “collecting instinct.”

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11