Wanamaker and the Columbians

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

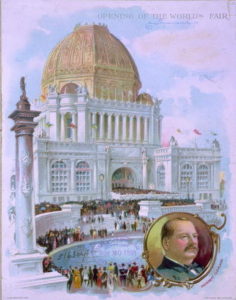

Opening of the World’s Fair, 1893, lithograph (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Opening of the World’s Fair, 1893, lithograph (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Until the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1892-93, nineteenth-century philatelists and societies functioned in a world almost completely removed from the producer of American stamps, the USPOD. Prior to the 1890s, the USPOD maintained limited contact with stamp collectors and produced a limited number of stamps. From 1847 to 1894, the USPOD contracted with five private firms that designed and printed all American stamps. The images on this early postage were most often the heads of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, with occasional appearances by Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, or other prominent white American politicians or military officers. Printing companies experimented with different aspects of the production process that led to pre-gummed paper, making it easier to affix one to a letter, and perforations between each stamp, making it easier to separate one from a sheet. Portraits of figures from the American past were the staple design genre of definitive stamp imagery. American stamps, unlike British one, never represented a living head of state. Meanwhile, postmaster generals were busy with balancing the duties of the Department with business interests of the press and big business and with morality crusades. Official records of USPOD reveal little contact with collectors. ((Alexander T. Haimann and Wade Saadi, “Philately, United States, Classic Period,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (National Postal Museum, May 11, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2027496; Peter T. Rohrbach and Lowell S. Newman, American Issue: The U.S. Postage Stamp, 1842-1869 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984). Overall, the USPOD records are very spotty in the late nineteenth century. Archivists from the National Archives note that federal records often are missing significant amounts of paperwork because there were no requirements to keep files indefinitely. Historians at the U.S. Postal Service concur that few stamp-related records exist from that era. Often records were legally destroyed. )) Conversely, philatelic journals did not discuss the USPOD much in their pages. Philatelic societies and journals functioned independently from the federal government. Publishing news releases regarding new issues of stamps was the only role the USPOD played in the philatelic press until the Columbian Exposition.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 One factor that muddied the relationship between collectors and producers was professional intermediaries who facilitated a philatelic economy outside of the government producing these stamps. Stamp dealers emerged in banking and business districts of major northern American cities during and after the Civil War particularly because Union stamps could be used as currency. Stamps could be an investment and liquidated if necessary, as happened during the War. Recognizing the commercial potential for selling and valuing stamps, the number of dealers grew and expanded into the southern cities of New Orleans and Atlanta. Private entities could trade in stamps that changed in value, but postal authorities could never sell stamps for anything greater than their face value. Postmasters could, however, sell stamps and stamped envelopes at a discount to certain “designated agents” who then had to agree to sell them at face value. ((Henkin, The Postal Age; Mary H. Lawson, “Philately in the United States,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&emd=1&mode=1&tid=2035125. “Act of June 8, 1872,” ch. 335, 17 Stat L. 305, reproduced in William Mark McKinney, Harold Norton Eldridge, and Edward Thompson Company, Federal Statutes Annotated, vol. VIII (Northport, New York: Edward Thompson Company, 1918), 132.)) While I will not address the particulars of the stamp market in this study, it is important to note how this private network formed outside of the government’s purview and flourished before postal agencies understood the breadth of stamp collecting’s popularity.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

John Wanamaker, 1889 (Photo from National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

John Wanamaker, 1889 (Photo from National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Retailer John Wanamaker, however, recognized these networks and forever changed the relationship between collectors and the USPOD during his tenure as Postmaster General (1889-1893) because he saw collectors as consumers of stamps. His administration is remembered most for implementing the Rural Free Delivery and postal savings plans, but Wanamaker also increased the visibility of the USPOD in the philatelic world. Known more as the creator of the modern department store than a Washington bureaucrat, Wanamaker brought his business acumen and understanding of customer relations to the Department. Additionally, Wanamaker was heavily influenced by the spectacle of the era’s world fairs, making it possible for him to see great potential in promoting the USPOD through a carefully designed exhibit at the Columbian Exposition that he envisioned would become part of a future postal museum. ((Robert Stockwell Hatcher, “United States Postal Notes,” American Philatelist 6, no. 11 (November 10, 1892): 185. John Wanamaker began and operated one of the first department stores in the U.S., Wanamaker’s, in Philadelphia. He forever transformed the retail business and was referred to as the “greatest merchant in America.” As Postmaster General, he spearheaded postal reform such as the Rural Free Delivery experiment, which some progressive reformers supported because of its capacity to unify the nation. William Leach argues that Wanamaker’s goal was to increase the public’s access to goods, subsidized by the government. Since he was a department store merchant, he favored other large-scale retailers, like Sears, Roebuck, and Company’s mail order business. See William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993), 32-5, 182-84. For Wanamaker’s fascination with World Fairs, see Herbert Adams Gibbons, John Wanamaker (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1971), 153-180; and United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1892 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1892), 74.))

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 From the early planning stages of the World’s Fair, Wanamaker envisioned heightening the postal service’s visibility by involving philatelic organizations to assist in staging an exhibit and by issuing the first series of commemorative postage stamps. Immediately after securing funding from Congress, the USPOD solicited the assistance of philatelists who eagerly cooperated soon after the announcement of the Exposition. Cooperating philatelists wished to display a complete set of all American stamps ever printed, and were shocked to learn that the USPOD did not keep samples from each printing. Seeing great potential to highlight philately at the Columbian Exposition, the American Philatelic Association (APA) encouraged wide participation among its members, emphasizing the great “impetus this exhibition will give stamp collecting!” ((Mekeel was interviewed in “Postage-Stamp Collectors,” New York Times, September 7, 1890. The government’s exhibit included stamped paper, models of postal coaches and mail equipment, photographs, maps, and examples from the Dead Letter Office. USPOD also operated a working post office where Columbians could be purchased at the Fair. Congress appropriated $40,000 for the postal station and an additional $23,000 for transporting the mail to and from the fairgrounds over the course of the Exposition. American Philatelic Association, Catalogue of the American Philatelic Association’s Loan Exhibit of Postage Stamps to the United States Post Office Department at the World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago, 1893 (Birmingham, CT: D.H. Bacon and Company, 1893), 3; Albert R. Rogers, “American Philatelic Association’s Exhibit of Postage Stamps at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893,” American Philatelist 7, no 3 (March 10, 1893): 33-5; Memo, “Inventory of Articles turned over to Mr. Tyler,” Albert H. Hall, “Letter to Hon. Wilson S. Bissell,” in RG 28, Records of the Post Office Department, Office of the Third Assistant Postmaster General (Stamps and Stamped Envelopes) Correspondence, 1847-1907 (Washington, DC: March 2, 1894); United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1892 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1892), 75-7.))

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Wanamaker was aware of the stamp collecting “mania” and wanted the USPOD to capitalize on philatelists’ desire to acquire new stamps and attract new collectors amazed by a beautifully-designed set of Columbians. Estimating that millions of collectors, from the “school boy and girl to the monarch and the millionaire,” kept stamps in collections “never (to) be drawn upon to pay postage,” Wanamaker saw great potential for profit. He designed the Columbians as limited issues, combined with a larger size and elaborate designs, many based on historical paintings to attract international dealers and collectors. Not just for collecting, Columbians held real postal value as pre-paid postage and did not replace the contemporary issue of stamps from that year. “Though not designed primarily for that object,” Wanamaker emphasized the profit-making potential of these commemoratives, which was “of highest importance to the public service.” He estimated that these stamps would bring in revenues to the federal government of 2.5 million dollars. ((United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1892 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1892), 75-7.)) He also saw that this practice was “in the line of a custom connected with national jubilees.” To justify the upfront expenditure on extra stamps, Wanamaker noted that the Treasury Department issued a souvenir coin of Columbus for this occasion—another way that government engaged with collectors of a federal commodity. In 1890 and 1891, USPOD deficits exceeded 5 million dollars annually, so Wanamaker’s estimation of Columbian sales would reduce those budget deficiencies. ((United States Post Office Department, Annual Report 1892, 77. For a comparison of budget deficits from 1890-1894, see United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1894 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), 3.))

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 A.D. Hazen, Third Assistant Postmaster General under Wanamaker, reiterated the importance of this special issue to encourage collecting and generate revenues for the USPOD. Referring to a past success when the Department issued commemorative envelopes for the Centennial Exhibition in 1876, he also saw revenue potential for the Columbians lying in dormant collections “without ever being presented in payment for postage,” proving “a clear gain to the Department.” Encouraging stamp collecting through the commemoratives not only cultivated “artistic tastes and the study of history and geography,” but led to a “more accurate knowledge of their postal system.” ((United States Post Office Department, Annual Report, 1894, 910-1100. Although it is unclear how citizens learned more about the postal system through these stamps, Hazen incorporated language already used by philatelists in promoting their hobby to outsiders, claiming stamps held an inherently educational value. Messages embedded in the stamp’s imagery were as important as selling those stamps. Wanamaker’s business acumen and zeal for increasing American’s access to goods logically led him, and the Department, to seek out new customers by experimenting with new products. He wanted the general public to voluntarily walk into post offices in their towns to purchase stamps, because of their design and stories told on stamps, when not mailing a letter.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Drawing heavily from historical paintings and sculptures, the Columbians demonstrated in their imagery that Columbus—even if the Exposition did not directly have much to do with him—symbolized utopian ideals of progress put forth in the construction of the White City and the Midway that celebrated empire and anthropologically-based racial hierarchies. ((Robert W Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 38–71.)) The stamp series offered an extensive visual narrative tracing Columbus’s life, beginning with his journeys to the Americas and his relationship with the Spanish Crown, told over sixteen stamps.

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

Columbian Series, 1-cent to 15-cent issues. Photographs courtesy of 1847 USA and National Postal Museum Collection.

Columbian Series, 1-cent to 15-cent issues. Photographs courtesy of 1847 USA and National Postal Museum Collection.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Printed across the top of each stamps were the years 1492-1892, with the words “United States of America” appearing immediately below. Americans were used to their stamps carrying the identifier, “United States Postage,” but adding the anniversary years to the stamp connected Columbus with the founding of the United States. In the series, while the United States of America may have been emphasized in print, only two of the sixteen stamps actually represented scenes in the Americas. Nine treated Columbus’s life in Spain and his relationship to the Spanish Crown, while three represented the journey across the Atlantic. Queen Isabella appeared in seven of the sixteen stamps, leading Americans to believe that Isabella’s influence on Columbus journeys could not be overstated. Additionally, Isabella and an unnamed American Indian became the first women represented on American stamps. ((Alexander T. Haimann, “Columbian Exposition Issues,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2027851. To see the entire series of Columbians on one page, see http://1847usa.com/identify/19th/1893.htm. )) That the USPOD’s stamp choices reflected themes of empire and conquest should come as no surprise, given that United States foreign policy was already embarking on what would become a sustained imperial endeavor.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Columbian Series, 30-cent to 5-dollar issues. Photographs courtesy of 1847 USA and National Postal Museum Collection.

Columbian Series, 30-cent to 5-dollar issues. Photographs courtesy of 1847 USA and National Postal Museum Collection.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 For the first time, the USPOD released a large limited-issue commemorative series, drawing considerable attention in the philatelic and popular press. Immediately after the Columbians’ release, philatelic journalist Joseph F. Courtney commented that the stamps were “the most magnificent pieces of workmanship” and very artistic. J.P. Glass wrote that collectors were “indebted for the handsomest, most interesting and most talked about series of stamps ever issued.” Philatelist and editor, Harry Kantner, delighted in the Columbian stamps, noting that they were “the cause of our progress” in lifting philately to “a higher point of popularity than it ever yet has attained.” ((Joseph F. Courtney, “Our Columbian Issue,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 3, No. 2 (January 1893): 33; Glass, “The Effect of the World’s Fair on Philately,” 9; and Harry F. Kantner, “Philately’s Progress,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 5, no. 1 (December 1893): 71. )) This heightened popularity was also due to increased press coverage highlighting the practice of stamp collecting. The New York Times featured an article on philately claiming that the new stamps gave “extra temporary impetus to the regular trade in stamps which has grown to proportions entirely amazing to persons not informed of its extent and diffusion.” This journalist also recognized a profit-making potential of the Columbians that proved “a lucky speculation on the part of the Government.” They brought “clean profit,” because the stamps would “be locked up in albums and never put upon letters for the Government to carry.” E.S. Martin wrote in his Harper’s Weekly column how the success of the Columbian stamps “called attention to the very lively status of the stamp-collecting mania.” So lively, that he noticed the presence of collected stamps in many homes was as prevalent as soap.((“Good as Chest Protectors,” New York Times, January 23, 1893; E.S. Martin, “This Busy World,” Harper’s Weekly, April 14, 1894.)) Most collectors would not have purchased the entire series but their presence—in post offices and in the press—heightened awareness of philately as a leisure time activity and no doubt encouraged more people to purchase a Columbian even if they had no intention of starting their own collections.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Americans—collectors and non-collectors—were most likely to buy and see 1- and 2-cent issues from the series, because those denominations paid for post cards and first-class mail, respectively. Though the series was large in quantity and contained a variety of issues, seventy-two percent of those printed were 2-centers. The first two stamps treated Columbus’s initial journey and landing. Based on a painting by William H. Powell, the 1-cent represented Columbus looking out to sea and sighting land from a circular vignette in the center for the stamp. ((Alexander T. Haimann, “2-cent Landing of Columbus,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2027853; Alexander T. Haimann, “1-cent Columbus in Sight of Land,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&tid=2027852. Powell was known for his historical paintings in the nineteenth century. Two paintings hang in the U.S. Capitol, Discovery of the Mississippi, and Battle of Lake Erie.)) The circle around Columbus may represent a round world—something he is most often credited with declaring—and offers the viewer a peak at Columbus as if we are looking at him through a ship’s spy glass telescope.

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

Columbus in Sight of Land, 1-cent, 1892-93 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Columbus in Sight of Land, 1-cent, 1892-93 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 On the exterior of the vignette sat three Native Americans, almost docile, already in a defeated position looking away from the viewer, wrapping their arms around their bodies as if in an effort to protect themselves and their families. The images of Columbus and others traveling on board ship with him were heavily robed and clothed, contrasting greatly with the natives awaiting their arrival. The woman and child were lightly covered with a single cloth draped over the mother’s legs. The man wore a smaller cloth covering his lower body and wore a headdress that appears to be more evocative of an American Plains Indian than of a Taino or other Caribbean native. These images visually foreshadowed and justified the conquest that followed Columbus’s arrival. This stamp’s representation of native peoples was not dissimilar to how American Indians and other non-whites were represented on the Midway Plaisance as savages and ethnologically inferior to those with Anglo-Saxon blood roaming the fairgrounds. ((Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, 55–65.)) Here, the stamp staged Columbus as the civilizer arriving in a savage land.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

Landing of Columbus, 2-cent, 1892-1893 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Landing of Columbus, 2-cent, 1892-1893 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 The 2-cent stamp, the most widely disseminated of all in the series, also was based on a historical painting that maintained Columbus as a founding father. John Vanderlyn painted the Landing of Columbus, which hangs in the Capitol Rotunda. It represents Columbus’s party landing, but unlike Powell’s imagery, this one did not include any native peoples. ((Haimann, “2-cent Landing of Columbus.”)) Their presence is erased as if they did not exist or were not important enough to be depicted in this painting-turned-stamp. Columbus touches the ground with his sword while he raises a Spanish flag and looks to the sky, claiming the lands in the name of Spain and perhaps invoking the will of God. Interestingly, the flags on the stamp appear intentionally blurry as if to obfuscate that they represented the Inquisition and the Catholic monarchs of Ferdinand and Isabella. The 2-cent celebrates Columbus’s “discovery” of seemingly unpopulated lands in the Americas, and does not attempt to connect how Columbus actually related to the founding of the United States as a nation—a connection that is implied with “1492-1892, United States of America” title printed across all of the stamps in the series. Instead, Columbus is a Christian civilizer.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Drawing upon the themes of triumphant human progress at the Exposition, the Columbians offered a post-Civil War story of American unity by representing Columbus’s journeys as America’s origins. Columbus did not land in territories that would become identified as the South or the North—Jamestown versus Plymouth. Unknown to most Americans at the time, Columbus landed in Caribbean islands that would become part of the United States following the 1898 war with Spain. Columbus’s imperialistic endeavors in the 1490s matched with the U.S.’s own actions in the 1890s. The stories, as retold in the stamps, obscured more complicated questions about conquest and slavery that followed Columbus’s landing and served to celebrate the conquest. As the struggles over who participated in and attended the Exposition demonstrated, the Exposition and the stamps commemorating the fair were meant for racially-white audiences. ((Rydell, All the World’s a Fair; Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982).)) Some of those citizens felt uneasy about their futures and took comfort in the utopian vision of the White City, while the stamps offered others a positive outlook on the American past during a time of economic crisis, Populist political debates, labor unrest, rapidly-expanding industry, Jim Crow laws, and rapid immigration. For newly-arrived immigrants, Columbus’s story as represented in stamps provided them with a visual national narrative of their adopted country.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 While attracting praises from collectors and non-collectors alike, others heavily criticized the release of the Columbians for the size of the series and size of the stamps. Senator Wolcott (R-CO) called for a joint Congressional resolution to discontinue the Columbian stamps, exclaiming that he did not want a “cruel and unusual stamp” unloaded on collectors. Wolcott criticized Wanamaker for acting in a mercantilistic manner by trying to profit from philatelists. ((The New Stamps Ridiculed,” New York Times, January 22, 1893.)) Correct about Wanamaker’s retailing instinct, Wolcott’s assumptions were slightly flawed because Wanamaker would not profit personally—only the government reaped any monetary benefits. If fiscally successful, the USPOD could better manage their finances and require less in appropriations from Congress.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 One major critique related to the stamps was the high monetary denominations. The one dollar issue, for instance, represented Queen Isabella selling her jewels to finance Columbus’s journeys, was never meant to pay for actual postage as the highest domestic rate in 1893 equaled ninety cents. This was true for each of the highest denominations in the series ($1-$5 issues). A Chicago Tribune story critiqued “Uncle Sam” for playing “a confidence game on confiding nephews and nieces” with the Columbians. Large denominations, such as the four- and five-dollar, would never be used for sending mail, but would be “hidden between red leather covers in stamp albums.” If a collector wanted to purchase the entire series, they paid $16.34, which in today’s dollars is roughly $300. ((“The New Stamps Ridiculed;” “Good as Chest Protectors,” New York Times, January 23, 1893; from Chicago Tribune, re-printed, “The Big Columbian Stamps,” New York Times, January 14, 1893; Haimann, “Columbian Exposition Issues.”)) While higher denominations might mail a heavy package overseas, these stamps essentially were designed specifically for collectors to buy and save. Dealers placed them on envelopes to create commemorative covers purchased by collectors, even though the dollar amounts far out-priced the cost of mailing a letter. ((Alexander T. Haimann, “1-dollar Queen Isabella Pledging Her Jewels,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2027864; Alexander T. Haimann, “4-dollar Queen Isabella & Columbus,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2027866.)) Critics saw stamp collectors as vulnerable individuals falling prey to John Wanamaker and the USPOD who wanted to milk the savings from stamp collectors by issuing this special postage. Concurrent concern over new department store-style consumerism that tempted customers into buying products they did not need may have colored the critiques.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Less concerned with being taken advantage of by the post office, some philatelists simply did not like the appearance and size of the stamps. One collector joked that he used Columbians for “sticking plaster” inside his house because the stamps were so large. This journalist noted that their “office boy” upon seeing the stamps exclaimed “what wrong have I committed that I should suffer this unjust punishment” for needing to lick multiple larger-than-normal stamp at one sitting which proved “doubly tiresome and detestful.” This tongue-in-cheek article was not nearly as biting as the other critiques of the commemorative issues, but the author admitted that merely one month after the release he was already tired of them. ((Col. U.M. Bus, “The Columbian Issue Criticised,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 3, no. 3 (February 1893): 53-4.)) Wanamaker’s stamp series definitely generated discussion about the stamps themselves, and he attempted to address the concerns of his critics.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Efforts to stop circulation of the commemoratives from circulation were unsuccessful, but Wanamaker’s successor, W.S. Bissel, curtailed the total number of pieces printed. Bissel found that the previous administration optimistically placed an order for three billion Columbian stamps to be sold over one year. He renegotiated the remaining contract down to two billion stamps and saved the Department nearly $100,000 in manufacturing costs. The cost for printing an equal number of smaller-sized ordinary stamps was nearly half that for printing the Columbians. According to Department figures, the rate of purchase for the commemoratives fell by mid-1893, and Bissel felt the collectors’ purchasing power was not as great as Wanamaker predicted. At the time, sales of stamped matter provided 95 percent of the USPOD total revenues. For fiscal year 1893, total postal revenues jumped by nearly five million dollars compared with 1892, but declined again by almost two million the following year. Increased expenses for printing the Columbians and the manufacture of a variety of new postal cards, in addition to escalating transportation costs, never allowed the Columbian sales to translate into postal profits. ((United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1892 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1893), xxvi-xxx, 463-73; and United States Post Office Department, Annual Report of the Postmaster-General of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1894, 479–490. The decline in postal revenues for fiscal year 1894 was mostly attributed to economic depression.))

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Despite not earning a profit for the Department, Wanamaker started a trend and the government continued to experiment with limited-issue stamps celebrating other expositions. The Columbians were notable not only as the first series of commemoratives, but also as a turning point for the Department to actively encourage stamp collecting as a hobby. Philatelists speculated about their positive influence on the hobby while others pointed directly to the Columbian issues as the reason they started collecting. ((“Philately’s Progress,” The Pennsylvania Philatelist 5, no. 1 (December 1893): 71; A. Pilley, “My Collecting,” Philatelic West 1 (June 1896): 1.)) The next set of commemoratives attracted extremely strong opposition from American and international philatelic organizations to the USPOD’s effort to issue another world’s fair series in 1898.

This chapter section is interesting because it demonstrates the authority exerted by the collector. While the USPOD has an agenda and a need, the way collectors respond to the stamps speaks to the unpredictability of cultural authority. Collectors may buy the stamps, but they may reject their “messaging.”