Stamps as Consumer Collectibles

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 As philatelists exposed non-collectors to their hobby in the 1880s, Americans began to view stamps as something other than postage. Collecting, in general, became increasingly accessible and acceptable to Americans as the culture of consumerism developed and was shaped by merchant capitalists, private and federal institutions, and advertising agencies from the 1880s to the 1930s. ((William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of A New American Culture (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993).)) In the 1880s, stamp publishers and tobacco companies printed chromolithographic trade cards and free postage stamps to advertise their products and attract customers. Many dry goods companies capitalized on new chromolithography technology and customized cards branded with the company’s name and products. These trade cards were a popular collectible in their own right because they came free in packaging and contained attractively colored images that belonged to sets, meant to be completed. Many children, particularly girls, collected and kept cards in scrapbooks; an activity that prepared girls especially, according to Ellen Gruber Garvey, to become keen and brand-conscious shoppers for their future households. ((Ellen Gruber Garvey, The Adman in the Parlor: Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture, 1880s to 1910s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996); Gelber, Hobbies : Leisure and the Culture of Work in America; Lisa Jacobson, Raising Consumers: Children and the American Mass Market in the Early Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004)). Trade cards that advertised stamp albums, associated stamps and related materials as consumer products to male and female consumers.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

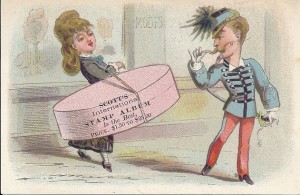

Scott’s International Stamp Album trade card, late 19th century (author’s collection)

Scott’s International Stamp Album trade card, late 19th century (author’s collection)

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Some trade cards advertised for stamp dealers and publishers, while others contained stamps and encouraged the collecting of the cards and the stamps. Scott’s Stamp and Coin Company used stock cards to advertise their most popular album. In the image above, we see the Scott’s imprint labels on the large clothing box, visually equating it with consumable woman’s clothing, and possibly expensive French clothing. Charles A. Townsend, a dealer in Akron, Ohio, stamped his name and address on the front of a series of famous persons cards, including President Buchanan and actress Pauline Markham. On the reverse side, Townsend printed a shortened price list of stamps he held in stock at the time. ((“Antique Stamp Dealer Trade Card Pauline Markham Bufford,” eBay, accessed August 16, 2009; “Antique Stamp Dealer Trade Card Pres. Buchanan Bufford,” eBay, accessed August 16, 2009)) Stamp dealers and publishers promoted their business in ways very similar to how other consumer goods merchants and manufacturers advertised their products in the late nineteenth century.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Rival tobacco companies competed for adult customers in the late nineteenth century by offering card sets with illustrations of presidents, baseball players, animals, and fish. In an effort to attract more customers into trying their cigarettes, W. Duke and Sons offered smokers a series of trade cards relating to postal matters that included a “genuine foreign postage stamp” in every box.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Sample trade cards with stamps printed by Duke Cigarettes ( John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library)

Sample trade cards with stamps printed by Duke Cigarettes ( John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library)

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 On the back of the cards, Duke told customers that these stamps were not only for “the beginner,” but the “owner of a large collection” would find stamps “such as he could never find before.” ((Ethel Ewert and Rachel K. Pannabecker Abraham, “‘Better Choose Me:’ Addictions to Tobacco, Collecting, and Quilting, 1880-1920,” Uncoverings 21 (2000): 79–105.; “Postage Stamps – Loose Cards,” Duke Digital Collections Item, 1880s, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/eaa.D0150/.)) Duke recognized that trade cards weren’t the only mass-printed items to be collected, so were stamps. Advertisers identified an emerging philatelic culture among men of certain economic means and hoped some of them might consider trying a Duke cigarette if they were already inclined to smoke and collect.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 To encourage saving stamps that accumulated from buying cigarettes, the Duke Company recruited a trusted name in philately, J. Walter Scott, to produce a beautifully designed album to hold the complete set of stamps available to Duke’s cigarette customers.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

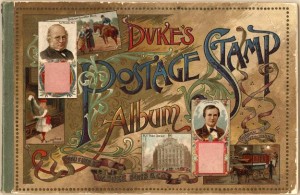

: Duke’s Postage Stamp Album, 1889 (John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library)

: Duke’s Postage Stamp Album, 1889 (John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library)

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Scott, who advertised his own albums, including the one pictured in the trade card above, endorsed this album as a legitimate philatelic product—something that club philatelists would easily recognize. In a letter printed on the album’s inside cover, Scott stated that Duke’s generosity in giving away stamps on cigarette cards “made this album a necessity.” Many who had “never seen a foreign stamp before have now become eager collectors.” An album was a necessity if one adhered to principles of philately that clubs and dealers promoted. The album forced an order so that new collectors learned to arrange the free stamps by country. Duke’s album represented a complete set of stamps to be distributed in cigarette boxes, which was not as large as Scott’s International albums that represented all known varieties produced and circulated in the world at a given time. While stamps offered their consumers an “educational advantage” because, according to Scott, stamps led people directly to the study of history and geography, this album cried out to be filled and encouraged consumers to smoke more cigarettes. ((W. Duke Sons & Co, Duke’s Postage Stamp Album (Durham and New York: W. Duke, Sons and Company, 1889), http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/eaa.D0003-01/pg.1/.; Ibid.; John Walter Scott, The International Postage Stamp Album, 8th ed (New York: Scott Stamp and Coin Co. Limited, 1886).)) As stamp collecting grew and clubs began to form, Duke Tobacco and Scott Stamp and Coin merged their capitalist interest to sell cigarettes and stamps in the 1880s.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 This advertising tactic, combining stamps and trade cards, may have counteracted criticisms Duke faced for circulating images of “lascivious” women on other card sets. Trade card advertising generally appealed to women, but tobacco cards clearly were meant for male audiences, even if others held onto the cards within a household. It would not be until the 1920s that cigarette companies acknowledged female smokers in their advertising campaigns. ((Nancy Bowman, “Questionable Beauty: The Dangers and Delights of the Cigarette Industry, 1880-1930,” in Philip Scranton, ed., Beauty and Business: Commerce, Gender, and Culture in Modern America (New York: Routledge, 2001), 52–86.)) Duke possibly experimented with offering stamps on a trade card because the company believed that stamp collecting as a hobby already appealed to a class of men with means.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10