Washington as Common Man

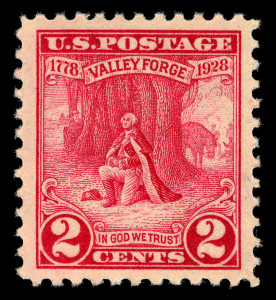

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 In contrast to the Lexington and Concord series which elevated the white citizen-farmer-soldier to the status of national hero, the 1928 Valley Forge anniversary stamp represented a mythical story about General George Washington that made him seem humble, like a common man.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Washington’s name and face were used by companies to sell many different products, such as taffy.

Washington’s name and face were used by companies to sell many different products, such as taffy.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 In the 1920s, Washington lived prominently in popular and political cultural as his name and face were used to market dishes, sell movies, and to justify immigration restrictions. Prior to the Sesqui, mail order catalogs sold colonial-themed, mass-produced knickknacks containing George’s image. One familiar scene was Washington kneeling in prayer at Valley Forge. A nineteenth-century print of this vignette, based on a painting by Henry Brueckner, circulated widely after the Civil War and again following World War I. A bas-relief of a similar image was installed at the YMCA West Side Branch in New York in 1904, and replicas were created and installed in churches, schools, and historical societies. Many viewed this print as visual evidence of Washington’s true piety, even though the image was completely contrived. Imagery that illustrated how a military leader turned to God for help in hard times was powerful. The scene was based on a tale first recanted by Parson Mason Weems in 1804. Weems perpetuated a cult of Washington through many stories he published about Washington including the myth about chopping down the cherry tree. ((For an excellent examination of the culture of Washington’s image, see Marling, George Washington Slept Here. Weems’s claims have never been proven and attempts to debunk this particular myth were published in 1926 during the Sesquicentennial. Mason Locke Weems, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington, Mt Vernon edition (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippencott Company, 1918), 234; James W. Loewen, Lies Across America (New York: Touchstone, 1999), 340. Some critiques of Washington myths were published by C.W. Woodward, George Washington, the Image and the Man (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1926); reviewed by James A. Woodburn, “Review: [untitled],” The American Historical Review 32, no. 3 (April 1927): 611–614; Lorett Treese, Valley Forge: Making and Remaking a National Symbol (University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).))

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Supporters of the anniversary encampment at Valley Forge wanted to incorporate this familiar image on a stamp and began petitioning the USPOD in the mid-1920s. Malcolm H. Ganser asked in a letter to the editor of the New York Times for other readers to write to a very reluctant Postmaster General to sway him into printing a stamp commemorating this event. Requests were honored and the image of Washington kneeling in prayer would represent the anniversary at the encampment even as Rupert Hugues and other historians began questioning the accuracy of that scene. One newspaper columnist opined there was “no good reason to doubt,” and another stressed that neither the stamp engraver nor historians were at Valley Forge with Washington, so why would he doubt Washington’s actions? ((Malcolm Ganser, “A Valley Forge Postage Stamp,” New York Times, January 20, 1928, 20.; “To Issue Valley Forge Stamp Of Washington at Prayer,” New York Times, May 4, 1928, 2; Harry Carr, “The Lancer,” Los Angeles Times, May 12, 1928, a1; “Valley Forge Stamp,” Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1928, b4.)) The myths of Washington were difficult to challenge in public.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Hughes was a biographer of Washington and was extremely critical of those wishing to mythologize Washington. Hughes and others criticized the stamp because they recognized that the government held immense power by endorsing images that stamp consumers might assume to convey historical fact. Interestingly, while Hughes was concerned about representations of the general and president, others were thankful that remembrances of the Revolution were not solely militaristic.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Battle of White Plains, 2-cent issue (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection

Battle of White Plains, 2-cent issue (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Other anniversary stamps, including Lexington-Concord (1925), the Battle of White Plains (1926), and the Burgoyne Campaign (1927) depicted battle scenes and images of soldiers, cannon, rifles, and powder horns. Postal officials approved of Washington kneeling as a way to please those seeking representations of the “spiritual” side of war. ((Hughes writes about the struggles he encountered as Washington’s biographer to discover Washington’s human and more complex self that often conflicted with myths of his infallibility. Rupert Hughes, “Pitfalls of the Biographer,” The Pacific Historical Review 2, no. 1 (March 1933): 1–33.; and “Stamp News: About Our Commemoratives,” The Youth’s Companion 102, no. 8 (August 1928): 418.))

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The stamp engraving is a voyeuristic view of Washington kneeling in prayer in the woods surrounding the Valley Forge encampment as if from the perspective of Issac Potts, who was shown hiding behind a large tree. According to Weems’s tale, Potts was delighted when he came upon Washington praying in the woods. Potts decided at that moment that he could support the Revolution because Washington demonstrated that one could be a Christian and a soldier without moral conflict. ((Marling, George Washington Slept Here, 1-8. In 1955, a stained glass window with Washington kneeling was donated anonymously and installed in the Prayer Room next to the rotunda as a reminder of the religious faith of the nation during the Cold War.)) This image provided a comforting message for some. Washington kneeling at Valley Forge also spoke powerfully to those who believed that the United Sates was not only a Christian nation, but one that benefited from the Grace of God during hard times.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Valley Forge Issue, 2-cent, 1928 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Valley Forge Issue, 2-cent, 1928 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Four printed words solidified the notion that the entire nation believed in God: “In God We Trust.” These four words distinguished this stamp from any others printed at the time. This phrase appeared on contemporary U.S. coins, but never on stamps. It would not be until another Red Scare in the 1950s when a stamp, this time a definitive, carried the motto. ((In 1954, a definitive issue of the Statue of Liberty carried the phrase, “In God We Trust” two years before it was adopted as the official motto of the United States. See Steven J. Rod, “8-Cent Statue of Liberty,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&tid=2028969.)) On the Valley Forge stamp, however, the phrase acts as a label interpreting the scene telling consumers that this is why we trust in God, because Washington trusted in God and the U.S. reaped the blessings of independence. Any debates over Washington’s religious beliefs or his aversion to prayer were settled in the minds of some Americans because the USPOD printed and circulated this interpretation of Washington’s private life.

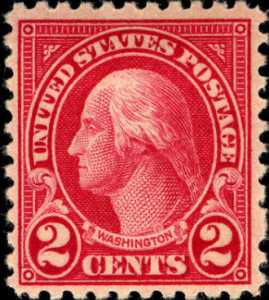

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 This stamp held great meaning for some, particularly the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). They included the Valley Forge stamp together with a collection of papers and objects in a copper box—together with a Bible, a copy of the U.S. Constitution, various DAR publications, including their immigrant handbooks, and signed cards by President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge—buried in the cornerstone of Constitution Hall in November 1928. ((“Mrs. Coolidge Lays D.A R. Stone With Old Washington Trowel,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 25, 1928, 6K.)) That this stamp was included in this time capsule further illustrates how powerful, and sometimes transitive, stamp messages could be. The representation of Washington as a pious man held value for the DAR because they believed they were upholding ideals held by descendents of Revolutionary War heroes. Washington’s actions and values were therefore theirs because their ancestors served under Washington. One could argue that a stamp was chosen to represent these connections to Washington because of its small size making it fit neatly inside a capsule. If true, the DAR easily could have purchased a definitive 2-cent stamp used every day by millions of Americans to send first-class letters with Washington’s portrait that had been a mainstay of U.S. definitives since the mid-nineteenth century. ((Rod Juell, “2-Cent Washington,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2033917.))

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Washington, 2-cent, definitive (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Washington, 2-cent, definitive (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Instead, they chose the Weems-inspired image of Washington in prayer.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 We can see from the Revolutionary War Sesquicentennial commemoratives that the UPSOD glorified individuals and selective battles to instruct Americans, immigrants, and international collectors as to what and who was important to remember. Other stamps reflected similar patterns in design and message. Common white men were the heroes, and leaders were not elites but rather depicted as strong men who walked among their soldiers, and sometimes prayed. Seeing these stamps representing Revolutionary War men motivated other heritage and hereditary-based groups to pursue commemoratives for their humble heroes.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14