Booker T. Washington and the Emancipation Stamps

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 During the struggle over the Anthony-suffrage stamp, the widely circulated African-American newspaper Chicago Defender asked, “How About Us?” Acknowledging that women ought to be represented on stamps, the paper pressed that there “should be some stamps bearing black faces,” as well. When the USPOD expanded its commemorative program in the 1920s, the Defender and many citizens called for stamps celebrating the heroism and achievements of Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Crispus Attucks. Bostonians hailed Attucks as a martyr who was remembered as the first casualty of the Revolution. Why wouldn’t he qualify as an American hero equal in valor to Nathan Hale, whose likeness appeared on a stamp in 1925? ((“By Way of Suggestion,” The Chicago Defender, May 9, 1925, A10; “How About Us?,” The Chicago Defender, June 7, 1930, 14; and Rod Juell, “1/2-Cent Hale,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://arago.si.edu/flash/?s1=5|sq=nathan%20hale|sf=0. For other petitions, see Design Files, stamps # 873 and #902, National Postal Museum.)) Many African Americans were frustrated that the postal service, and their government, continued to ignore the achievements of people of color.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Major Richard Robert Wright, Sr (public domain photograph)

Major Richard Robert Wright, Sr (public domain photograph)

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The most ardent supporter of a Washington stamp was Major Richard Robert Wright, Sr, an accomplished former slave who fought in the Spanish-American War, served as the first president of the Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth (now Savannah State University), and founded the Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company in Philadelphia. With a seemingly sympathetic administration in office, Wright began petitioning President Roosevelt and Postmaster General Farley in 1933 and regularly wrote scores of letters through 1939. By the mid-1930s, as the number of commemoratives grew at a rapid rate, African American newspapers again called on the government to choose Washington, Attucks, or Douglass for a stamp. The Defender asked fellow citizens across the country to write personal letters to Farley requesting a Washington stamp. Momentum also was building for a Frederick Douglass stamp, pushed by another commemorative committee that also waited and waited for the Department to choose their African American hero. The secretary of Dunbar High School’s stamp club in Washington, DC appealed to President Roosevelt asking for a stamp honoring “members of the Negro race” because “we are loyal citizens and always answer when our country calls, regardless of the discriminations we are forced to suffer.” ((N. S. Noble, “The Constitution’s Stamp Corner,” The Atlanta Constitution, February 10, 1935, 2K; “Write Mr. Farley and Ask Him about the Stamp Issue,” 5; Arthur Whaley, “What About a Stamp?,” The Chicago Defender, December 25, 1937, 16; and Herbert A. Trenchard, “The Booker T. Washington Famous American Stamp (Scott No. 873): The Events and Ceremonies Surrounding Its Issue,” The Ceremonial, no. web issue no. 4 (n.d.): 8–11. Wright’s efforts to publicly celebrate African American freedom did not end with this stamp but included conceptualizing National Freedom Day. Ethel Valentine to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, January 25, 1938, Design File, stamp #902,National Postal Museum.)) Constantly reminded of their status as second-class citizens, some African Americans fought for a stamp as a small step along a long road to achieving full political equality. Achievements made by African Americans would gain legitimacy when representing the United States on a stamp.

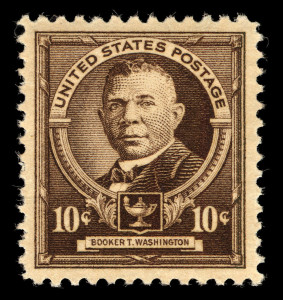

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 In July 1939, the USPOD announced that Washington’s image would appear as part of the series honoring thirty-five “Famous Americans.” Though not honored separately like Anthony, the Washington stamp was lauded as a victory by African American leaders because it finally broke the color barrier imposed on postage subjects. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Washington was the most-widely recognized African American, so it comes as no surprise that he was the first black person to earn a stamp. Known internationally for founding the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Washington created a path for African Americans in the rural south to achieve economic equality through mastery of trades and skills first, before agitating for full political and social rights. Often described as an accommodationist, Washington was an acceptable representative of African American achievement to many white Americans who believed in racial segregation and the genetic inferiority of African Americans. His approach, thought to be very practical, was acceptable to many southern African Americans. Conveniently, Washington’s philosophy was also acceptable by the federal government who would soon ask African Americans to fight in another world war for a country that did not allow them full rights as citizens. ((Louis Harlan, “Booker T. Washington and the Politics of Accommodation,” in John Hope Franklin and August Meier, eds., Black Leaders of the Twentieth Century, Blacks in the New World (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982), 1-18.))

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Three months after this announcement, the Diamond Jubilee of the Emancipation Proclamation event in Philadelphia celebrated the printing of the Washington stamp. Postal officials attended this “grand” celebration, and Major Wright and Mary McLeod Bethune, a prominent civil rights leader and advisor to FDR as a member of the Federal Council on Negro Affairs, were on hand. They distributed miniature busts of Washington to white and black children who attended, representing more than five hundred public schools in the Philadelphia area. ((Kent B. Stiles, “Releases Honor 35,” New York Times, July 23, 1939, XX10; “Stamp Victory,” The Chicago Defender, September 16, 1939, 19; “7,000 Celebrate Issuance of Booker T. Washington Postage Stamp in Philly,” The Chicago Defender, October 7, 1939, 19.)) These busts served as physical reminders of Booker T. Washington’s self-declared legacy as one who raised himself “up from slavery” and would not agitate for social equality. Celebrating these two events together with a mixed-race audience gestured to Washington’s autobiography where he recalled that newly-freed slaves felt no bitterness towards their white masters upon hearing the Emancipation Proclamation read. Whites and blacks came together in another symbolic gesture during the ceremony as four girls—two black, two white—marched on stage in military costumes, carrying an American flag that they then draped across the shoulders of Major Wright “in token of his victory in securing” the Washington stamp. ((Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery, An Autobiography (New York: Doubleday, Page, and Company, 1919), 21; Louis R. Harlan, The Booker T. Washington Papers, vol. 3 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1974), 538–87; “7,000 Celebrate Issuance of Booker T. Washington Postage Stamp in Philly,” 19.)) The multi-racial audience and participants appeared to “cast down” their buckets in a joint celebration of Washington’s work.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 This was a significant symbolic moment indicating that an African American was worthy of representing the entire nation and population by appearing on a stamp. Wright’s successful efforts created a space where an African American stood equally alongside white Americans in the catalog of US stamps, and opened the door for other black heroes to earn a place in the official narrative of the American past told through commemoratives.

¶ 7

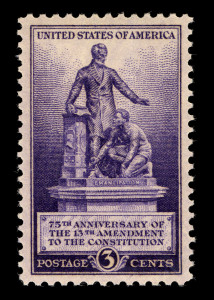

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

Booker T. Washington 10-cent, Famous American series, 1940 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

Booker T. Washington 10-cent, Famous American series, 1940 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Washington was selected as one of five educators in the Famous American series that also recognized achievements of authors, poets, scientists, composers, inventors, and artists. Designed as one in series, Washington’s stamp appeared similar to others with only the portrait and ink color distinguishing each issue. Washington’s engraving came from a familiar photograph where he looks outward from the stamp. While the Washington was colored brown, it was in keeping with the colors established for other 10-cent stamps in this commemorative series. Washington’s 10-cent issue was the highest priced stamp in the group of five educators honored in the series. Major Wright and others worried that the price might hinder purchases from African Americans. Despite his concerns over the higher price, the Washington was one of the most widely-sold (twenty-three million dollars worth) stamp in the Famous Americans series. ((“Farley At Tuskegee Same Day ‘Booker T.’ Stamp Goes On Sale,” The Chicago Defender, January 6, 1940, 12; “Stamps in Educators Group of Famous American Series,” New York Times, February 8, 1940, 20; and Trenchard, “The Booker T. Washington Famous American Stamp (Scott No. 873): The Events and Ceremonies Surrounding Its Issue.”))

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 The Washington stamp was first released and sold at the Tuskegee Institute’s Founder’s Day celebration on April 7, 1940 that brought postal officials together with the Tuskegee community. At the celebration, Postmaster General Farley sold the first Booker T. Washington stamp together with the Tuskegee Philatelic Club. Farley spoke at the ceremony hailing Washington’s legacy as a “pioneer educator” and spokesman of his race. The Defender devoted tremendous amounts of copy to the events at Tuskegee by publishing photographs and large portions of the speeches. According to Farley, “Negro progress” could be traced directly to Washington’s “humanitarian work, noble ideals, and practical teachings” that he put into place at Tuskegee. Importantly, according to Farley, Washington taught that “merit, no matter under what skin was in the long run recognized and rewarded.” His other greatest achievement was in “his interpretation of his people to the white men,” read as his accommodationist approach to the fight for political equality. To compliment Washington’s dedication to training young people of the south, Farley, drew a jarring parallel between Washington’s “refusal to accept personal gain with that of Robert E. Lee.” Farley furthered the comparison by weaving into his speech a statement by Lee about his strong obligation to train young men of the south after the Civil War. According to Farley not “one word of that declaration need be changed were the speaker Booker T. Washington.” Not surprisingly, the Defender omitted this portion of the speech. ((“3,500 Hear Postmaster Farley At Tuskegee,” The Chicago Defender, April 13, 1940, 9; “Farley Praises ‘Mr. B. T.’ As ‘Negoro Moses,’” The Atlanta Constitution, April 8, 1940, 2; “Farley Opens ‘Booker T.’ Stamp at Tuskegee,” The Chicago Defender, April 13, 1940, 1; “He Couldn’t Hate,” Christian Science Monitor, April 19, 1940, 22.))

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Farley cleverly connected Washington’s work with that of Robert E. Lee during this first day ceremony for an audience of Americans not attending the Tuskegee events. One can imagine that a few gasps were heard in the audience upon Farley drawing such a comparison. Perhaps anticipating angry letters from white southern citizens, Farley explained that Washington was another southern leader who devoted himself to bettering the lives of the region’s young people. To make the Washington stamp acceptable to white southerners, Lee, the hero of the “Lost Cause,” (honored a few years earlier on postage) was called upon to make Washington’s achievements also appear equally heroic.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Booker T. Washington stood equally distinguished alongside fellow Famous Americans, however, the stamp commemorating the seventy-fifth anniversary of the signing of the Thirteen Amendment issued the same year looked backwards. News of this stamp came as a surprise to many as the USPOD announced the printing only one week before it was available for sale during the final days of the New York World’s Fair in October 1940. Generally, the Department announced commemorative stamps at least a few months before their printing to allow for first day ceremonies to be planned and to build anticipation from collectors and the petitioning communities or commissions. ((W. Bloss, “The Stamp Album,” C4; Special, “13TH Amendment Stamp to Be Issued,” The Chicago Defender, October 12, 1940, 4; “President Praises Negroes at Fair,” New York Times, October 21, 1940, 20; “Emancipation Stamps Are Result Of A Long Fight,” The Chicago Defender, October 26, 1940, 1.)) By debuting at the World’s Fair, the USPOD missed an opportunity sell and promote the stamp earlier that year at the American Negro Exposition in Chicago that celebrated seventy-five years of freedom. Black achievements were celebrated while federal agencies and private corporations demonstrated concern for African American welfare through agricultural, housing, and employment exhibits. The USPOD was one of the agencies that staged a small exhibit to sell the Washington stamps—and easily could have sold the Thirteenth Amendment issue. Additionally, the World’s Fair was rife with racial tensions. At the Fair’s opening in 1939, African Americans protested a lack of representation in the fair’s planning, management, and exhibits. ((Robert W. Rydell, World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 157-192.))

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Labeled as a “New Deal masterstroke,” the stamp was released just prior to the presidential election of 1940. While all commemoratives represented someone’s agenda, this one in particular appeared to be politically motivated by FDR. Major Wright was delighted because he had been working for nearly a decade, petitioning for both an African American figure and a emancipation stamp. Wright wanted a 3-cent stamp specifically, because it could be used to mail a first-class letter, which happened to be the same denomination as the Anthony and other single commemoratives issued during the Farley administration. While various ceremonies celebrated this diamond jubilee of the Emancipation Proclamation, the true anniversary was of the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. ((W. Bloss, “The Stamp Album,” C4; “13TH Amendment Stamp to Be Issued,” 4; “President Praises Negroes at Fair,” 20; “Emancipation Stamps Are Result Of A Long Fight,” 1.)) Wright’s vision for celebrating emancipation as an uplifting and powerful moment in American history was not realized in the imagery chosen for this stamp.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Thirteenth Amendment, 3-cent, 1940 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

Thirteenth Amendment, 3-cent, 1940 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 During the first-day release ceremony, President Roosevelt used the stamp as a vehicle to praise African Americans’ achievements after slavery, even when the image chosen to represent emancipation was actually one of subservience. The stamp featured an engraving of the Freedmen’s Memorial depicting Lincoln standing over a kneeling slave, bowing at Lincoln’s feet, struggling to break the chains of bondage. Although financed partially by freed slaves, a white commission controlled the sculpture’s construction and chose a design representing emancipation as a generous act of moral leadership by Lincoln and enfranchised whites. Supposedly honoring freedom from bondage, the sculpture as composed by artist Thomas Ball did not represent a newly-freed slave figure on equal ground with Lincoln. The slave figure was still breaking away from slavery with no symbols of hope designed into the memorial to indicate that freedmen could ascend to a position of equality promised by emancipation. Given to the city of Washington in 1876 by the “colored citizens of the United States,” the memorial reasserted racial hierarchy in which descendants of slaves would always be inferior to white men. (( Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1997); Rydell, World of Fairs, 157–90.)) In choosing this image to commemorate emancipation with the Freedmen’s Memorial, the USPOD celebrated Lincoln, not freedom and equality, but instead a racial order in which descendants of slaves could never realize full equality in the US.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Choosing to commemorate the Thirteenth—and not the Fourteenth Amendment, that gave all adult males full rights of citizenship—seemed deliberate, to focus attention on the abolition of slavery and not on citizenship equality. Similar to the choice of Washington, the USPOD chose Lincoln to represent black freedom by printing a non-threatening stamp that also did not challenge the authority of state laws that legalized segregation. ((Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves, 89-128.)) Complicating the matter was FDR’s speech read at the Fair. In addition to lauding achievements of African Americans who had “enriched and enlarged and ennobled American life,” his language emphasized the need for American unity as he gestured toward the war in Europe. Liberty was “under brutal attack” and peaceful lives were challenged by “brute force” that would “return the human family to that state of slavery from which emancipation came through the Thirteenth Amendment.” Through this celebration, he called Americans to “unite in a solemn determination to defend and maintain and transmit to those who shall follow us the rich heritage of freedom which is ours today.” ((“President Praises Negroes at Fair,” 20.)) FDR rhetorically ignored the fact that the entire “human family” was not enslaved until 1865, but it was very specifically reserved for those of African descent. For FDR, the emancipation stamp was not a celebration of freedom for African Americans, much like the statue representing emancipation, but rather a call for unity under the false pretense that all Americans were created equal.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Prior to these stamps, the absence of African Americans symbolized their lack of political power. The publication signified a slow shift in nationalized political and cultural agitation. This shift, of course, was not without many contradictions in implementation. During FDR’s administration, African Americans did not benefit equally from New Deal-funded programs as whites because of the ways federal programs were constructed and implemented at a local level. At the same time, civil rights groups began publicizing their agendas more loudly and making their fight more visible to federal officials and the general public. Labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph threatened to march on Washington in 1941 to demand an end to racial discrimination in the defense industries and in the military. FDR partially conceded to some of Randolph’s demands by signing Executive Act 8802 in June 1941, which ended discrimination in the defense industries and federal defense positions. Randolph cancelled the march, but FDR never desegregated the military. Individuals like Randolph laid groundwork for additional legislation and executive orders to come that slowly repealed legal segregation. ((Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks; and Executive Order 8802, accessed July 17, 2009, http://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/index.html?template=print&dod-date=625.))

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 1 Both stamps printed in 1940 illustrated the contradictory ways the US government treated African Americans. As the individual achievement of Booker T. Washington—as an educator and not as a political figure—was revered in April, African Americans, as a race, were reminded in October that their freedom and equality still depended on whites. The Washington issue directly honored the achievements of one man and gestured toward millions of people defined and segregated by their race, yet the emancipation stamp reinforced racial hierarchies that prevented former slaves from achieving equality. The Thirteenth Amendment stamp, coupled with Washington’s, sent a message that the federal government approved of individual but not racial group achievement. FDR demanded desegregation of private industry but did not desegregate the military. Even so, FDR deftly combined Washington’s and Lincoln’s images as symbols of American progress to pave the way toward asking African Americans to work hard for a greater cause, and he alluded that their skills, labor, and duty would be rewarded with full equality under the law.

Comment awaiting moderation