Susan B. Anthony and the Military Series

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 In the early twentieth century, the USPOD positioned themselves as producers of historical narratives representing the American past, and laid a foundation that privileged the stories of elite white men. Citizen petitioners worked to break that foundation during the 1920s and 1930s, demonstrated by the Polish American campaigns to honor Pulaski and Kosciusko in an earlier chapter, and by women and African Americans who simultaneously campaigned for commemoratives to make their political achievements visible to collectors and non-collectors alike.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Until the late 1930s, US commemorative stamps almost exclusively honored the achievements of white men. When reading the corpus of commemoratives, women and all people of color played almost no role in US history. This is not surprising given the “Great Men” approach to teaching history in schools and presented in historical sites, but it also reflected contemporary discriminatory laws, practices, and violence directed against people of color and women. Petitioners for stamps honoring Susan B. Anthony and Booker T. Washington were astute observers of USPOD stamp production and understood that the government almost exclusively honored white male contributions in commemoratives. The stakes were high for these stamp supporters. As a result, they positioned the achievements of Anthony and Washington in the context of other commemorative issues and hoped that federal approval was a small step in a very long battle to achieve full political equality.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Commemorating the work of suffrage activists through a postage stamp was a key piece of a broader agenda for the National Women’s Party (NWP) and the Susan B. Anthony Memorial Committee. Committee Chair, Ethel Adamson, noticed great public honors were bestowed on men “for much smaller achievements” than Anthony’s and believed that her suffrage legacy, deserved public recognition. Some of the federal neglect, supporters suggested, could be repaired by issuing of a stamp honoring Anthony. Groups of women met with Third Assistant Postmaster General Eilenberger in 1934 and in 1935 to persuade him to accept their petitions to print an Anthony or a suffrage stamp. He did not support the stamp and claimed that stamp collectors showed no interest either. Even during the 1930s, white men comprised the memberships in philatelic associations. Speaking to philatelists at the American Philatelic Society’s annual convention in 1934, Eilenberger maintained that the USPOD wanted to “revive the memories of historic events” with the commemoratives, and dismissed rumors that his department might print a stamp honoring a women, including actress Mae West. ((Ethel McClintock Adamson, “Letter to James Farley, Postmaster General,” June 22, 1934, Design Files, Stamp #784, National Postal Museum; Edith H. Hooker, “Letter to the Post Master General,” February 6, 1935, Design Files, Stamp #784, National Postal Museum.; Clinton B Eilenberger, “Memorandum,” June 12, 1934, Design Files, Stamp #784, National Postal Museum.; all in Design Files, stamp #784, National Postal Museum; Eilenberger, “Speech Delivered to American Philatelic Society,” 4–6.))

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Before the fight over an Anthony issue, collectors of American stamps most likely held a few images of women in their albums. In the Columbian commemorative series, Queen Isabella of Spain appeared on six stamps and an unidentified native Caribbean woman sat on the 1-cent. A portrait of Pocahontas dressed in English clothing, mistakenly represented as royalty, was printed on the 5-cent issue in the Jamestown Exposition series (1907). In 1902, and again in 1922, the USPOD released a series of definitive stamps and they chose Martha Washington’s face as the first “American” woman to grace the 8-cent (1902) and 4-cent (1922) issues. Persons and places represented in these everyday stamps from 1922 were selected to “stand for America as it might be viewed by a newly arrived immigrant.” According to Third-Assistant Postmaster General Glover, the Department chose Washington over other possible well-known American women, including Anthony and Clara Barton, because she “more nearly typified the women who were closely identified with the ground-work of American national life in its first phases.” Washington was known as a wife and mother, not as a nurse and organizer or political activist like Barton or Anthony. Selecting Washington as the first woman represented on an stamp sold everyday freed the USPOD from any controversy, because few would argue against choosing the country’s original First Lady.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Still fighting for a stamp in 1936, women campaigning for an Anthony were outraged when they heard that the Department planned to print a series of stamps honoring US Army and Navy commanders, including Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Former president Theodore Roosevelt initiated the idea for a stamp series honoring American military heroes during World War I, but it was not until his cousin Franklin pushed for it that the series was approved. In February 1936, a list of military heroes was leaked after Secretary of War George H. Dern submitted his proposal to Roosevelt and the Postmaster General. Prior to any stamp printing, citizens began to react. Letters flooded the Department and the White House mainly from Southerners who supported a stamp honoring Robert E. Lee. Other letters, such as one from New York Congresswoman Caroline O’Day remarked that Republican women of her state would not like seeing Lee representing the United States on a stamp in the series. She noted that politically it would be important for elected officials to support the initiative, because the negative reaction from southerners would be far greater if there was no stamp honoring Lee. (( Marszalek, “Philatelic Pugilists,” 127-138.))

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

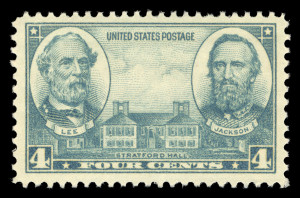

Lee-Jackson, 4-cent, Army-Navy Series, 1936 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

Lee-Jackson, 4-cent, Army-Navy Series, 1936 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 A long fight over the Army-Navy issues soon ensued. Images of military leaders from the Army and Navy were printed in a ten-stamp series that were released in small sets during 1936 and 1937. Each service received a set containing 1- through 5-cent denominations. Proceeding somewhat chronologically, the 1-cents honored Generals Washington and Greene and Captains Barry and Jones and continued through the War of 1812, Civil War, and Spanish-American War. While the series was planned in advance, the release of the Grant-Sherman-Sheridan in February 1937 and the Lee-Jackson in March drew the biggest public responses once the stamps were printed. Southern Congressmen, collectors, and interested citizens decried Sherman as a “common murderer” and defended Lee as a wronged hero who was unintentionally demoted by the Post Office because the stamp showed his uniform’s shoulder boards carrying two stars instead of three. Protests against the Confederate generals became battle cries for the Anthony committee and African American newspapers asking for a stamp honoring Booker T. Washington because “he has surely done more for American Democracy than Gen. Lee or Stonew(a)ll Jackson.” ((Gordon Trotter, “Army and Navy Issue,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, November 27, 2007), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2033175. Interestingly, the 3-cent denominations pictured Union Civil War Generals Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan and Admirals Porter and Farragut. Confederate Generals Lee and Jackson appeared on the 4-cent Army stamp while its naval counterpart featured Admirals Dewey, Sampson, and Schley, who commanded fleets during Spanish-American War battles. The 5-cents represented the service academies at Annapolis and West Point. “Write Mr. Farley and Ask Him About the Stamp Issue,” The Chicago Defender, April 10, 1937. I will address with the Booker T. Washington stamp later in this chapter.)) The USPOD stood squarely amidst a cultural debate over political equality and the legacy of the Civil War in the 1930s. Commemoratives representing Confederate officers acted as another attempt by the FDR administration to use stamps to promote nationalism, but these stamps were read as a clear rejection of political equality promised at the end of the Civil War. By appearing on US stamps, Lee and Jackson were not traitors, but American war heroes who looked out from postage equally alongside the portraits of George Washington, William Sherman, and Ulysses S. Grant.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Protectors of Susan B. Anthony’s legacy were also disturbed: “Why should such men, fighting for the principle contrary to our present standard of life and liberty, be given honors in advance of an individual who gave her services freely for the cause of freedom for all of the people—men and women alike?” According to the Chair of the National Women’s Party (NWP), the Department was not impressing women voters and urged Postmaster General Farley “to be fair with your women constituents and glorify some of our outstanding women with Susan B. Anthony leading them all.” Understandably, members of the NWP could not reconcile the contradictions of their government that honored men who led a secessionist fight against the Union and fought for oppression and slavery, while ignoring the accomplishments of one woman who represented the struggle for female voting rights. While the NWP often ignored voices and concerns from African American women, the party leader’s rhetoric indicated that they and Anthony fought for equality for all persons. Releases of the first issues in the Army-Navy series coincided with further indecision by Farley about an Anthony stamp. The Anthony Memorial Committee believed Farley kept “giving the women the run-around” by misleading them as to when the USPOD might issue an Anthony stamp: “First, we are too early, now we are too late.” The timing was never right, and seemed like an impossible battle to win. ((Nancy F Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987); and Alma Whitaker, “Sugar and Spice,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1936, A6.))

¶ 9

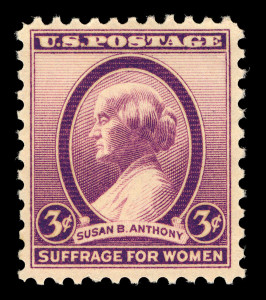

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Susan B. Anthony, 3-cent, 1936 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

Susan B. Anthony, 3-cent, 1936 (Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Amidst the military series debates, the Post Office Department announced in July 1936 that it would print a suffrage anniversary stamp using the portrait of Susan B. Anthony in August. The stamp’s engraving was drawn from a bust sculpted by Adelaide Johnson that represented her as a classically-inspired figure. Johnson described her sculpture as “expressing the entire life of Miss Anthony” by emphasizing her strength and spirituality. The stamp engraving depicts Anthony’s left profile with her hair wrapped into a bun in the center of the stamp. A wide oval frame encases her portrait making the vignette look like a cameo. Wearing cameo brooches became popular in the Victorian age, recalling the classical Greek art form of carving figures in stone relief. Many female cameo figures created for brooches were dressed in flowing robes with their curly hair pulled back from their faces. ((Monica Lynn Clements and Patricia Rosser Clements, Cameos: Classical to Costume (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1998); James David Draper, Cameo Appearances (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008).)) Anthony’s clothing was not necessarily flowing and her hair was not curly, yet her image alludes to the form of a cameo that presents an idealized female figure inside representing virtue. In choosing this style of image, Anthony is not an annoying agitator, but rather, a non-threatening, admirable citizen. The stamp’s purple ink aided in the stamp appearing like a cameo brooch, even though all 3-cent stamps were tinted violet. For example, in the Army-Navy series Admirals David Farragut and David Porter appeared on a violet 3-cent stamp. In contrast, however, the stamps of military heroes represented their bodies mostly looking outward from the stamps. Unlike other 3-cent single issues from the 1930s, the Anthony was cut to a smaller size and shape similar to a definitive stamp. Other single-issue commemoratives, such as the Texas Centennial (March 1936), Rhode Island Tercentennial (May 1936), and Ordinance of 1787 Sesquicentennial (July 1937) were rectangular in shape and distinctive as a commemorative. ((A series of definitives that were printed in 1938 featured profiles of presidents whose images were almost all drawn from busts. “Stamp May Bear Anthony Bust By Artist Here,” Washington Post, July 15, 1936, X6; Gordon T. Trotter, “Susan B. Anthony Issue,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, November 27, 2007), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2033174; Encyclopedia of United States Stamps and Stamp Collecting, “Presidential Series (1938),” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2033221.)) With its monetary value equaling postage for mailing a first-class letter, this Anthony-suffrage commemorative stamp actually appeared in size and functioned very similarly to a definitive. This was as close to a regular issue stamp as possible.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 NWP members and other supporters of Antony’s legacy and an equal rights amendment believed the stamp’s production was a real political victory. The USPOD, however, drew substantial criticism for their decision to print a stamp honoring Anthony from citizens and collectors alike. Since the stamp commemorated the sixteenth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, some believed honoring an oddly-numbered anniversary should not be eligible for a commemorative, unlike a twenty-fifth, fiftieth, or centennial. Some collectors questioned Farley’s rationale for printing an excessive number of commemoratives throughout this tenure, and specifically questioned his choice of Susan B. Anthony. One Washington Post reader warned of an “epidemic” brought on by the Anthony stamp that would open the door to the printing of stamps honoring Booker T. Washington, Esperanto, Babe Ruth, Al Capone, and former summer Olympian Eleanor Holm Jarrett. ((“Women Honor Susan Anthony At District Fete,” Washington Post, August 27, 1936, X13; Millicent Taylor, “For Our ‘Furtherance,’” Christian Science Monitor, August 26, 1936, 7; “Women Join to Hail Susan B. Anthony,” New York Times, August 27, 1936, 23.; “Is Anthony Stamp a Commemorative? Philatelists Call NRA Sticker ‘Orphan,’” Christian Science Monitor , September 15, 1936, 3; C.N. Wood, “Farley Stamps,” Washington Post, August 9, 1936, B7. In addition to Booker T. Washington, this string of unacceptable candidates for stamps included Ruth, a Catholic baseball player; Capone, an Italian gangster, and Eleanor Holm Jarrett, an Olympic swimmer who was kicked off the team before the 1936 Berlin games for excessive drinking—the worst offender according to Wood. Jarrett was married to a band leader and danced on stage with the band, occasionally in her bathing suit. Later she appeared in a few films in the late 1930s.)) Wood expressed his displeasure that the Post Office moved beyond honoring white, native-born men as representatives of American history to include what he saw as undeserving figures. Wood marginalized the accomplishments of Anthony and Washington in particular. John Pollock, then Chair of the Democratic Party, wrote to Farley indicating that some of his members might even leave the party in protest over the Anthony stamp. He warned Farley that if he did not suppress the Anthony stamp, Pollock guaranteed “it will prove a political boomerang.” Despite these warnings, the stamp did not damage Roosevelt’s chances of winning re-election, and Farley kept his job as Postmaster General. ((John Pollock, “Letter to James A. Farley, Postmaster General,” July 21, 1936, Design Files, Stamp #784, National Postal Museum; A W Bloss, “The Stamp Album,” Los Angeles Times, October 20, 1940, C4; “Women Honor Susan Anthony At District Fete,” X13; Taylor, “For Our ‘Furtherance,’” 7; “Women Join to Hail Susan B. Anthony,” 23. Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism.)) As a handful of commemorative subjects slowly interjected American stories outside of that exclusive white male perspective, some citizens rejected the stamps as ahistorical as a screen for their. These negative reactions showed that even working for a stamp was a political battle, one these women continued to wage through the mid-twentieth century.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 That debates over the military series and the Anthony stamp played out in government offices, philatelic meetings, mainstream media, and political organizations further illustrates the power Americans believed stamps held to circulate messages. Petitioners worked with sense of urgency to earn stamps for their cause, because they understood that the USPOD held power to spread historical and political ideas, and that those stamps would be saved by collectors. Importantly, stamps carried a federal endorsement of a particular narrative. Women and African Americans understood that they needed representation of their stories on stamps as they pushed for political equality. Congressional resolutions were submitted to the Postmaster General that did not win approval, including one in 1935 authorizing a stamp commemorating the “romantic settlement” of Indian tribes in Oklahoma that would honor Chief Sequoya, inventor of the Cherokee alphabet. ((Rodgers, H.J.Res. 153 (House of Representatives, 1935). A stamp was printed in 1948 honoring the “Five Civilized Tribes”: http://arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&tid=2028812)) Who was missing from the commemorative corpus was as important as who was represented. The USPOD controlled a platform where citizens, collectors, and federal officials negotiated meaning of contemporary cultural and political issues.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Anthony was not the first woman engraved on a stamp, but it could be said that she was the first politically-active woman chosen. Another would not be chosen until the 1940 Famous American series when Jane Addams and Frances Willard were honored with stamps together with thirty-five Americans honored for their achievements in the fields of literature, music, education, and technology. ((Alexander T. Haimann, “Famous Americans Issue,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (National Postal Museum, March 20, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2028610.)) Among those honored in this series was Booker T. Washington, the first African American pictured on a US stamp. The USPOD understood that issuing commemorative stamps brought great joy to petitioners, but that not all Americans, non-collectors and collectors, approved of the USPOD’s choices. This may be why the USPOD slipped Washington into a large series of stamps comprised of men and women famous for diverse accomplishments to avoid backlash and make Washington more acceptable to white Americans.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13