Humble Heroes of the Revolution

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

Sesquicentennial Exposition Issue (Photo: Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

Sesquicentennial Exposition Issue (Photo: Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Commemorations of persevering pilgrims figuratively gave birth to Revolutionary War heroes who fought for freedom against British oppressors as represented in stamps. Starting in 1925, a flurry of activity surrounded the 150th anniversary of the American Revolution that included many regional and local celebrations held across the United States. Following the lead of the pilgrim anniversaries, local committees petitioned their legislators seeking commemorative stamps and coins to recognize regionally-significant battles and heroes. The House Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures grew tired of such requests for commemorative coins. Responding to a request for a silver half dollar celebrating the Battle of Bennington and the independence of Vermont in 1925, the Chair noted the committee did not favor “legislation of this class, because of the great number of bills introduced to commemorate events of local and not national interest.” ((Albert H. Vestal, “Coinage of 50-Cent Pieces for Anniversary of Battle of Bennington” (Congressional Record, 1925). )) Anniversaries of local interest, however, continued to win commemorative stamps.

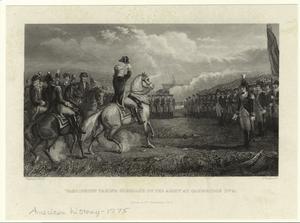

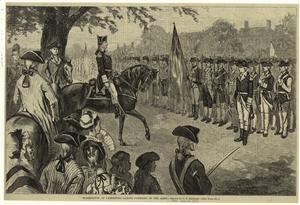

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

High Street 1776, Pageant, Costumed Colonial Musicians (Photo City of Philadelphia, Department of Record Archives, PhillyHistory.org)

High Street 1776, Pageant, Costumed Colonial Musicians (Photo City of Philadelphia, Department of Record Archives, PhillyHistory.org)

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The national Sesquicentennial celebration in Philadelphia in 1926 encouraged a colonial revival, not only of design and style, but in storytelling through stamps. Surprisingly, while the pilgrim anniversaries yielded small stamp series each, the “Sesqui” exposition itself did not. No narrative was told across three issues, leaving the Liberty Bell—the iconic symbol of the fair—to stand in as the only symbol of independence. Beginning in 1925, the USPOD told the story of the Revolution over fourteen stamps, or stamp series, related to these anniversaries. ((A large replica of the bell adorned with electric lights was built near the entrance to the exposition and considered a highlight for visitors. The bell appeared on the stamp and on a commemorative coin. Read more about the Sesquicentennial in the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/sesquicentennial-international-exposition/, Erastus Long Austin, The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition: A Record Based on Official Data and Departmental Reports (Philadelphia, Pa.: Current Publications, 1929) and Gordon Trotter, “Sesquicentennial Exposition Issue,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, November 19, 2007), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2032940.))

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Images from the Revolutionary War issues often represented portraits of victorious generals and elite soldiers or engravings of battle scenes. This was the case for the Lexington and Concord stamp series printed in 1925 that ushered in the anniversary celebrations. The Department released the stamps on April 4 to long lines of interested collectors and citizens waiting to purchase these stamps in Massachusetts. Ceremonies commemorating the skirmish were celebrated in and around Boston in April where salutes were fired and Paul Revere’s ride into Boston was re-enacted on April 19 and 20th during Patriot’s Day festivities. ((“New Postage Sale Starts Saturday,” Boston Daily Globe, March 31, 1925, A2; “Throngs at Post Office for Lexington Stamps,” Boston Daily Globe, April 4, 1925, A3; “Elaborate Program Arranged for Lexington’s Celebration,” Christian Science Monitor, April 9, 1925, 1.))

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Unlike other series, the Lexington and Concord commemoratives did not proceed chronologically by denomination. The 1-cent represented Washington assuming command of the Continental Army in Cambridge months after the initial skirmish. It was followed by a 2-cent depicting the actual confrontation, and the 5-cent completed the series memorializing the minuteman soldier. ((Roger Brody, “Lexington-Concord Issue,” Arago: People, Postage and the Post (Washington, D.C.: National Postal Museum, May 16, 2006), http://www.arago.si.edu/index.asp?con=1&cmd=1&mode=1&tid=2033846)). The image of Washington taking command of the continental army in Cambridge on the stamp was a conglomerate of nineteenth-century prints depicting this scene.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 Those prints, however, chose to represent Washington on horseback, while Washington stood among his soldiers on the stamp. This interpretation argues that Washington was a man equal to his soldiers, standing as a fellow citizen, even as he is set apart because he was not equal in rank or status.

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

Washington at Cambridge, 1-cent, 1925 (photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Washington at Cambridge, 1-cent, 1925 (photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Ready for war, the collected armies are dressed uniformly while one company marches in the right of the scene and another larger company stands at attention in the background. The viewer is led to believe that the Continental Army organized soon after the first confrontation and was prepared for combat.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Based on a painting by Henry Sandham, the 2-cent issue borrowed this victorious vision of the battle. ((Proceedings of Lexington Historical Society and Papers Relating to the History of the Town (Lexington, MA: Lexington Historical Society, 1890), xi–xii, http://www.archive.org/details/proceedingsoflex05lexi.)) The stamp mislabels the painting as “The Birth of Liberty,” while it is titled “The Dawn of Liberty.” Sandham painted the minutemen as a disadvantaged band of soldiers on foot who engaged the British in battle who charged on horseback.

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

Birth of Liberty, 2-cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Birth of Liberty, 2-cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 The minutemen appear larger in size but smaller in number in the foreground, standing victoriously with their arms in the air, shaking fists at the enemy, who appear smaller in size and larger in number, to be retreating in the background. This painting contrasts drastically with the vision etched by contemporary artist, Amos Doolittle, in May 1775.

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Doolittle represented the small band of minutemen in disarray after the first shot was fired as they scattered across the Lexington green in retreat. From other sources available, this representation seems to more accurately describe the events at Lexington. Other engravings by Doolittle show the British forces dominating, such as this view of Concord.

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 While the British eventually retreated to Boston after a standoff in Concord, the colonist did not defeat the British. Both sides exchanged fire and lost lives in this brief skirmish. Accuracy, however, was irrelevant to local history enthusiasts and residents who believed in the town’s centrality to the Revolution’s narrative as its birthplace. The Lexington Historical Society purchased Sandham’s painting in 1886 to hang in their town hall, and this scene was an integral part of their local history. ((David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). For an excellent close reading of the 2-cent stamp with the Amos Doolittle print, see “Why Historical Thinking Matters,” interactive presentation, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University, and School of Education, Stanford University, Historical Thinking Matters, available online at http://historicalthinkingmatters.org/why/.)) Embedded in the residents’ memory was that their fictive ancestors were a victorious band of volunteer soldiers who held off the well-trained British and forced a retreat. This image of local importance circulated across the country and the world and confirmed what most schoolchildren learned as part of the War for Independence narrative.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Prior to the 150th anniversary, poems written by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow cemented this mythical interpretation of Lexington and Concord in American memory during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. An engraving of Daniel Chester French’s “The Minute Man” statue, dedicated in 1875, appeared on the 5-cent stamp that also included the first stanza of Emerson’s 1837 poem, “The Concord Hymn.” Emerson composed the poem for one commemoration ceremony and later, it was engraved at the base of French’s statue commemorating the battle’s centennial. Most stamps include few words other than “U.S. postage,” relying on the imagery to illustrate the stamp’s theme. By reprinting the first stanza of Emerson’s poem, readers of the stamp, most of whom would never see the statue in person, understood the symbol. Emerson’s words would have been very familiar to many Americans because “A Concord Hymn” often appeared in textbooks and school readers. The government endorsed this vision celebrating humble, inexperienced, and “embattled farmers” who “fired the shot heard around the world.” ((Brody, “Lexington-Concord Issue”; Full text is available from the Poetry Foundation, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/175140. Emerson’s poem was sung at the dedication of another battle monument on July 4, 1837. These words were thought so moving that they were included in The Minute Man statue by French. Bessie Louise Pierce, Civic Attitudes in American School Textbooks (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1930), 204, http://www.archive.org/details/civicattitudesin00pierarch.))

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 French’s monument was similar in design to that of the common-soldier Civil War memorials erected in municipalities across the country in the late nineteenth century. Civil War memorials crafted as standing soldiers holding a rifle, not embattled, remembered those who fought and died in the 1860s and transformed into places for honoring all veterans. In the case of the “Minute Man,” though the physical statue stood in Massachusetts, once on a stamp, its representation became a national symbol of the earliest citizen soldiers who fought for independence. It was the stories of these men “who helped free our great and mighty country” represented on postage that collectors like Thomas Killride spoke of in his poem, “My Stamps.” ((Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1997), 162–208.; and Killride, in Phillips, Stamp Collecting, the King of Hobbies and the Hobby of Kings,407-08. Interestingly, Daniel Chester French earned a commemorative stamp of his own when he was included in the Famous American series’ artists grouping issued in 1940. )) Civil War monuments acted in ways to unify the country by focusing on the individuals who fought rather than the reasons for fighting. During the Revolutionary War, northern and southern colonies fought together, even if it was for a loosely-knit union. In 1925, the Massachusetts Minute Man acted as a unifying figure for celebrating white male citizenship throughout the U.S.

¶ 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

The Minute Man, 5-cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

The Minute Man, 5-cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Consumers of the Minute Man commemorative saw in the stamp design that this figure was to be remembered as a heroic freedom fighter. All commemorative stamps become miniature memorials once saved by collectors, but this particular stamp was designed to look like a memorial. The stamp represents the original sculpture and then frames it as if French’s piece was part of a large Neo-Classical memorial. Unlike the statue that stands in a field in Concord, the Minute Man on the stamp is flanked by two Doric order columns and two tablets bearing verses from Emerson’s hymn as if the verses are commandments, giving the statue the appearance of standing in an architectural niche. A niche highlights the figure inside it, and very often the figure is one to be worshipped or revered. Reverence of the Minute Man is reinforced with lighter shading behind the statue’s head on the stamp that draws the eye in to focus on an archetypal American hero.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Like physical memorials, commemoratives do not allow space for questioning of the subject’s interpretation. The Battle of White Plains and Vermont Sesquicentennial issues in 1926 and 1927 continued the theme of citizen soldiers as battle heroes. Unnamed, without military uniforms, men fought and represented the Green Mountain Boys in Vermont, for example, to defend their territory against British forces. In these stamps, and in the spirit of the commemorations, the white citizen-farmer-soldier stood as the archetypal American hero.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22

0 Comments on paragraph 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23

0 Comments on paragraph 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24