Pilgrims and Origins

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 A new era in commemorative stamps began in 1920 with the Pilgrim Tercentenary, as the variety of commemorative subjects expanded beyond promotions of world’s fairs to include significant anniversaries, military victories, and heroic individuals. The Pilgrim Tercentennial celebrated the landing of religious separatists on Cape Cod and their eventual settlement in the town of Plymouth, Massachusetts. From December 1920 through the summer of 1921, towns in many states organized pageants and parades to commemorate this anniversary. The stamp series created for this event was not the first to represent America’s founding mythologies (see the Columbians, 1892-93, and the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition,1907); the series was significant because it sparked interest from many citizens to ask the USPOD to highlight their community’s history and connections to America’s origins on stamps. ((For examples of states planning activities see, Benjamin Roland Lewis, Pageantry and the Pilgrim Tercentenary Celebration (1620-1920) with Sample Pilgrim Pageants,suggestions for Programs, Bibliographies, Etc., for the State of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah, 1920), available, from Hathi Trust: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t6vx0qb15. For reporting of the events, see Chronicling America, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/search/pages/results/?date1=1836&rows=20&searchType=basic&state=&date2=1922&proxtext=pilgrim+tercentenary&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1&sort=relevance )) As a reflection of contemporary politics, elected officials and patriotic-hereditary groups invoked the legacy of Plymouth pilgrims both to assert the primacy of Plymouth as America’s birth place, and to speak to local and national anxiety over immigration in the 1920s.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Organized after World War I during a time when many US citizens were in favor of severe restrictions on immigration, the Pilgrim Tercentennial events highlighted perceived differences among good and bad immigrant groups. Poems and speeches glorified the legacy of the Massachusetts pilgrims as nation builders and model immigrants, in contrast with a widely-held belief that immigrants in the twentieth century tore apart an imagined American fabric. Plymouth was proclaimed to be the “corner stone of the Nation,” by Mayflower descendant Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who detailed how the pilgrims’ success against adversity allowed for America to grow into a great nation. ((Charles A. Merrill, “Urges Revival of Pilgrims’ Faith,” Boston Daily Globe, December 22, 1920, 1.)) Vice President Thomas Marshall also touted the achievements of the “pilgrim fathers” who “prepared the way” for “the birth of a new and mighty world.” He used the opportunity to argue for immigration restrictions advocating that contemporary immigrants needed to follow the example set by pilgrims and commit to staying in US rather than merely coming to work and returning home. According to Marshall, the pilgrims came to America “to worship God and to make homes, determined never to return to Europe.” ((“Urges Bar on Aliens,” Washington Post, February 20, 1920, 10.))

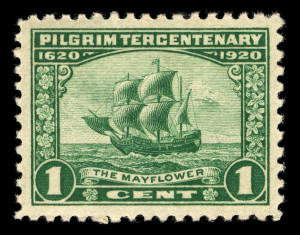

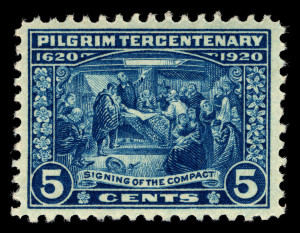

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The stamp designs commemorating the celebration promoted the pilgrims’ cultural legacy as America’s first founders. Interestingly, none of the three postage stamps printed in the series contained the identifying words, “U.S. Postage,” which all other stamps prior and since carried. This cemented the story of the pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth as quintessentially American, as it needed no marking as US postage. Even the U.S. Mint’s commemorative anniversary coin imprinted the words “United States of America” on the front of the half-dollar coin. ((Brody, “Pilgrim Tercentenary Issue.” To view an image of the commemorative coin, see <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pilgrim_tercentenary_half_dollar_commemorative_obverse.jpg>))

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Philatelists noticed this omission, concerned—and interested—that it might be an error in the printing, but the USPOD did not recall the stamps because the design was intentional. Editors of American Philatelist were disappointed with the series, claiming that the 2- and 5-cent issues were far too crowded with figures and decoration to be enjoyed. ((Editor, “New Issue Notes and Chronicle,” The American Philatelist 34 (January 1921): 150.))

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Mayflowers, fittingly, flanked each stamp’s scene, and like the Columbians, the Pilgrim Tercentenary series formed a short narrative. The story began on the 1-cent stamp with the Mayflower sailing west across the ocean on its journey with no land in sight—origin or destination.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

Pilgrim Tercentenary, 1-cent, 1920 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Pilgrim Tercentenary, 1-cent, 1920 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Similar to the Columbians, the landing occurs in the 2-cent stamp–the most commonly-used stamp to mail a letter and remained the standard rate of first-class postage until 1932. ((Jane Kennedy, “Development of Postal Rates: 1845-1955,” Land Economics 33, no. 2 (May 1957): 96.; and Andrew K. Dart,“The History of Postage Rates in the United States since 1863,” September 26, 2008 (http://www.akdart.com/postrate.html). First-class postage temporarily increased to 3-cents from 1917-1918 during American involvement in World War I.)) This stamp’s engraving makes the landing look harsh, unexpected, and jolting for the party at Plymouth Rock. Men, women, and children huddled together illustrating that family units migrated to the New England coast. Although this image suggests that struggles lie ahead for the settlers, the rock is what grounded the travelers, and is the object that grounded those celebrating the anniversary in the past. Plymouth was the ceremonial ground in 1920 and provided the physical connection to the past events.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Pilgrim Tercentenary, 2-cent, 1920 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Pilgrim Tercentenary, 2-cent, 1920 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 The journey’s symbolic end revealed itself in the 5-cent where the Mayflower Compact was signed indicating permanence, and showed the first document of self-governance in what would become the United States. Copies of the Compact were printed and distributed for the Tercentenary. Divine right blessed this settlement as the central figure pointed towards the light illuminating the signing. Drawn from a painting by Edwin White, the signing image illustrates families migrating together even though only men signed the document. ((One effort to circulate the Compact was by the descendants: George Ernest Bowman,The Mayflower Compact and Its Signers, with Facsimiles and a List of the Mayflower Passengers (Boston: Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1920): https://archive.org/stream/mayflowercompact00bow#page/n19/mode/2up. The 5-cent, “Signing of the Compact” stamp, is a miniature engraving based on an Edwin White painting from 1858. William Bradford may have been the main figure in this painting, since he is pictured in the U.S. Mint’s half-dollar commemorative coin also issued for this anniversary. White specialized in American historical painting, including Washington Resigning His Commission which was commissioned to hang in the Maryland State House. To see a copy of Washington Resigning his Commission, see http://www.msa.md.gov/msa/speccol/sc1500/sc1545/e_catalog_2002/white.html.)) The scene emphasizes that there was a community, comprised of family units, who crafted the Mayflower Compact and pledged to work together.

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

: Pilgrim Tercentenary, 5-cent, 1920 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

: Pilgrim Tercentenary, 5-cent, 1920 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 At the time of the anniversary, New England preservationists and genealogists argued that the Plymouth pilgrims were the true first Americans because family units arrived together to form a permanent settlement through signing the Compact, unlike the commercially-mind individuals who sailed to Jamestown. By representing this scene, the Tercentennial committee reiterated their argument and wanted all Americans to consider Plymouth as the birthplace of the America.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Virginians and New Englanders regularly argued over the true origins of the American story and which settlements contributed more to the development and character of the United States. Post-Civil War regional tensions can be read in written evidence found in newspapers and journals such the William and Mary Quarterly (WMQ). In 1909, shortly after the tercentenary celebration of Jamestown’s founding, Virginia historians refuted declarations published by members of the New England Historic Genealogical Society that there were “radical differences of character and influence” between Mayflower descendants and Jamestown settlers, because Plymouth “subordinated the commercial spirit (of Jamestown) to that of securing ecclesiastical and political freedom for themselves”—seen in the 5-cent. WMQ responded that those charges were “so gross, so unprovoked, so untrue,” and the statement of such freedoms and strength of character in the north were exaggerated. ((“Jamestown and Plymouth,” The William and Mary Quarterly 17, no. 4 (April 1909): 305–311. Interestingly, this piece ends with a nod of middle ground by specifically pointing to the “present enlightened North” who condemned the “ruinous” policies of Reconstruction, signaling that there was hope in settling these sectional disputes around the fictional “natural law” of white supremacy—made visible in many cultural articles in post-Reconstruction US.))

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Rivalries die hard, and Virginians did not let the Pilgrim Tercentenary pass without reminding Americans of their claim to the origins and contributions to American politics and governance. One address given at the College of William and Mary noted that Virginia’s contributions to the forming of the United States were far greater than any other state, but that Massachusetts came in second place. During the national celebration of the New England pilgrims, this effort reminded Americans that the “first” settlement was at Jamestown. ((Alton B. Parker, “The Foundations in Virginia,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 1, no. 1 (January 1, 1921): 1–15. )) No one at this time, recognized other colonial settlements in the western U.S. or acknowledged that the original residents of “America” were native peoples who were displaced, attacked, manipulated, and feared by European colonizers.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Virginians and New Englanders weren’t the only ones wrestling over founding stories publicly, through representation on stamps, as descendants from other European “pilgrims” argued successfully for their stories to be told on commemoratives.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15