Norweigan Pilgrims

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 The Norse-American Centenary stamp series provides another example of how the government endorsed a narrative of ethnic pride proposed by a regional commemorative committee. Much like the Huguenot-Walloon stamps, this series promoted a regional celebration of another group of pilgrims whose event committee desired the stamps to be one piece of a large festival honoring first-waves of immigrants. The Norse-American Centennial Committee secured a Congressional Joint resolution that commended Norwegian immigrants for contributing to the “moral and material welfare of our Nation.” They were credited with settling the “great Midwest,” rather than pouring into cities, crowding them, like contemporary immigrants were doing in St. Louis, Chicago, and other midwestern cities. ((Representative Kvale, Joint Resolution (HJ 270), Authorizing Stamps to Commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the Landing of the First Norse Immigrants, 1924, Congressional Record 65 (May 26, 1924), p.9581.)) Imagery and narratives presented by the Centennial committee sought to connect the story of Norwegians in America to a heroic past that could be traced to Vikings such as Leif Erikson, whose arrival in the New World predated Columbus and the Plymouth Pilgrims. The Pilgrim Tercentennial influenced how the Norse-American Centennial Committee shaped their message and why the committee rooted the message in celebrating pioneer fathers and their (debated) status as religious pilgrims. Like many other immigrant communities, the Centennial Committee balanced celebrating their distinct Norwegian heritage and culture, while also claiming their piece of the American past by earning a place on federal stamps. ((April Schultz, “‘The Pride of the Race Had Been Touched’: The 1925 Norse-American Immigration Centennial and Ethnic Identity,” The Journal of American History 77, no. 4 (March 1991): 1265–1295. Whether the Norse sloop carried religious refugees or not was under some debate. One article in the New York Times spread those claims in the popular media: E.Armitage McCann, “Uncle Sam Honors His Norse Family,” New York Times, October 11, 1925. A scholarly article published the same year argued against the assertion that Quakers on the sloop fled Norway because of persecution. As Henry Cadbury argued, the Norwegian government exaggerated the story of fleeing Quakers to slow the rate of Norwegian immigration to the United States in the 1840s. Norwegian officials passed a law granting religious tolerance to all of its residents in 1845. See Henry J. Cadbury, “The Norwegian Quakers of 1825,” The Harvard Theological Review 18, no. 4 (October 1925): 293–319.))

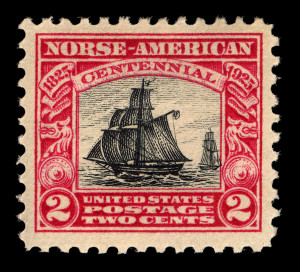

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Following the convention of earlier stamp series, this set emphasized the immigration and a journey across the Atlantic as way to assert status as original immigrants, distinguishing their stories of migration from that of new immigrants arriving in the U.S. in the early twentieth century. On the 2-cent, Restaurationen, “the Mayflower of the Nosemen,” carries the first Norwegian immigrants to the United States, sailing west across the stamp without land in sight on July 4, 1825. ((Joint Resolution (S.J. Res 133), “Authorizing and Requesting the Postmaster General to Design and Issue a Special Postage Stamp to Commemorate the Arrival in New York on October 9. 1825, of the Sloop Restaurationen, Bearing the First Shipload of Immigrants to the United States from Norway; and in Recognition of the Norse-American Centennial Celebration in 1925,” January 3, 1925. ))

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

Norse-American Centennial, 2-cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Norse-American Centennial, 2-cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

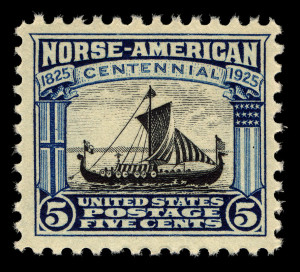

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The second stamp does not represent the landing, but, rather, the 5-cent issue featured an engraving of a Viking ship built for the Columbian Exposition. That ship sailed from Norway to Chicago to remind fairgoers and stamp consumers in the 1920s that Norwegian explorers visited America long before Columbus, the English-Dutch Pilgrims, the Huguenots, or the Walloons. This particular image, interestingly, pointed the ship’s bow toward the east, or toward the homeland. On the stamp, the Viking ship sails from a banner or shield of Norway towards one of the United States and the Norse-American Viking ship is flying colors similar to an American flag.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Norse-American Centennial, 5 cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

Norse-American Centennial, 5 cent, 1925 (Photo, National Postal Museum Collection)

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 These stamps were in high demand from collectors because of the design and intensity of the ink colors and sold out. The USPOD received letters requesting the issues be reprinted. Postal officials regretted that they had to treat all commemoratives consistently and could not reprint this series alone because they would hear protests from other groups claiming the Norwegians received preferential treatment. ((Design Files (#621))) In this case, the USPOD understood that the subject matter represented on the stamp held great meaning for petitioners—past and future—and citizens. Postal officials were careful to balance the sensitivities of commemorative scenes chosen with interests of some collectors who focused more on the particulars of stamps’ designs and artful quality of the production.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Descendants of these early European settlers wanted to demonstrate that their immigrant ancestors were good immigrant-citizens and worked to transform the U.S. into a great and prosperous nation. Difficult to read in the stamps’ images, these feelings were expressed by the Norwegian-American commemorative committee who wanted to celebrate ethnic pride, but designed the celebrations to focus on messages of good citizenship and patriotism. Even the planning committee and other Norwegian Americans involved with the Centennial felt conflicted over the messages of the celebration. Many Norwegians opposed American involvement in World War I and faced nativistic attacks, not as severe as German-Americans, but strong enough to identify their group as outsiders. By 1925, Norwegian communities in the northern midwest still debated how to balance Americanization and ethnically-constructed heritage activities. ((Bodnar, Remaking America, 55–61.; and Schultz, “The Pride of the Race Had Been Touched.”)) Through public commemoration, Norwegian-Americans of the midwest declared that they were nation builders like the pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. And with an episode of their past represented on commemorative stamps, the reach of their story stretched far beyond Minnesota.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7